Vijay Marottar regrets nothing more than the last conversation he had with his father.

It was a humid summer evening, and their village in Yavatmal district was slowly fading into the twilight. He had set out two dinner plates for his father and himself in their dimly-lit hut – two neatly folded rotis, lentils and a bowl of rice.

But his father, Ghanshyam, took one look at the plate and lost his cool. Where were the diced onions? His reaction was out of proportion, according to 25-year-old Vijay, but quite in character at that time. “He had been cranky for a while,” he says sitting on a plastic chair in the open space outside their one-room hut in Akpuri village in Maharashtra. “Little things would set him off.”

Vijay did go back to the kitchen and sliced the onions for his father. But an unpleasant argument broke out between the two after dinner. Vijay went to bed that night with a sour taste in his mouth. He had hoped to make up with his father the next morning.

But the morning did not come for Ghanshyam.

The 59-year-old farmer consumed pesticides that night. He passed away before Vijay woke up. It was April 2022.

Vijay Marottar outside his home in Akpuri in Yavatmal district. What he regrets the most is the last conversation he had with his father, who took his own life in April 2022

Nine months after his father’s death as he speaks to us, Vijay still hopes to rewind the clock and undo that unpleasant conversation between them on that fateful night. He tries to hold on to Ghanshyam’s image as a loving father and not the anxiety-ridden man he had become in the few years just before his death. His mother, Ghanshyam's wife, had passed away two years ago.

His fathers’ anxiety had a lot to do with the family’s five acres of farmland in the village, where they traditionally cultivated cotton and tur . “The last 8 to 10 years have been particularly bad,” says Vijay. “The weather has been increasingly unpredictable. We have a late monsoon and a prolonged summer. Every time we plant the seeds, it is like throwing the dice.”

That uncertainty made Ghanshyam, a farmer for 30 years, suddenly unsure of his abilities to do the only thing he knew well. “Farming is all about timing,” says Vijay. “But you can no longer get it right because the weather patterns keep changing. Every time he planted the crop, a dry spell followed, and he took it personally. When it doesn’t rain after sowing, you must decide whether or not to go for the second round,” he adds.

The second round of sowing doubles the basic production cost, but one hopes for a harvest that would still deliver returns. Most of the time, it doesn’t. “In one bad season,” says Vijay “we’d lose anywhere between 50,000 to 75,000 rupees.” Climate change has led to variations in temperature and precipitation, reducing farm income by 15-18 per cent for irrigated areas, according to the OECD’s Economic Survey of 2017-18 . The losses, the survey states, could be as high as 25 per cent in non irrigated areas.

Ghanshyam, like most small farmers in his region of Vidarbha, could not afford expensive irrigation methods and relied entirely on a good monsoon, often inconsistent. “It doesn’t drizzle anymore,” says Vijay. “There is either a dry spell or flooding. The uncertainty in the climate impacts your decision-making ability. It is extremely stressful to farm in these circumstances. It is unsettling and that is what made my father cranky,” he adds.

'It is extremely stressful to farm in these circumstances. It is unsettling and that is what made my father cranky,' says Vijay as he explains the uncertain weather, crop failures, mounting debts, and mental stress that took their toll on his father's mental health

The perpetual feeling of being on tenterhooks and the eventual loss have triggered a mental health crisis among farmers in the region, which is already known for extreme agrarian distress and an alarming number of farmer suicides.

In India, close to 11,000 farmers ended their lives in 2021, and 13 per cent of them were from Maharashtra, says the National Crime Records Bureau . The state continues to have the highest share of people who died by suicide in India.

Yet the crisis is far deeper than the official numbers convey. As the World Health Organisation (WHO) says, “for every suicide, there are likely 20 other people making a suicide attempt.”

In the case of Ghanshyam, the family’s consistent losses due to erratic weather had led to huge debts. “I knew my father had borrowed from a private moneylender to keep our farm afloat,” says Vijay. “The pressure to repay had weighed on him as the interest increased with time.”

A few farm loan waiver schemes that had come up in the past 5 to 8 years had several conditions. None of them covered private moneylenders. The stress related to money was an albatross around their neck. “My father never told me how much money we owed. He had taken to drinking heavily in the last couple of years before he died,” Vijay adds.

Two years before Ghanshyam's death in May 2020 his wife Kalpana died at 45 of a sudden heart attack. She was also under duress with their worsening financial condition

Alcohol abuse is a symptom of depression, according to Praful Kapse, 37, a psychiatric social worker based in Yavatmal. “Most of the suicides have an underlying mental condition,” he says. “It goes untraced because farmers don’t know where to get help for it.”

Ghanshyam’s family saw his worsening struggle with hypertension, anxiety and stress before he finally ended his life. They had no clue what to do. He wasn’t the only one in the house struggling with anxiety and stress. Two years ago in May 2020 his wife Kalpana, all of 45 years old with no prior health condition, had died of a sudden heart attack.

“She looked after the farmland and the household as well. And because of the losses, it had become difficult to feed the family. She was tense because of our worsening financial situation,” says Vijay. “I can’t think of any other reason.”

Kalpana’s absence made it worse for Ghanshyam. “My father was lonely and went into a shell after she died,” says Vijay. “I tried talking to him, but he would never share his feelings. I guess he was just trying to protect me.”

The post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fear and depression are more prevalent in rural regions suffering from extreme weather events and unpredictable climates, argues Kapse. “Farmers don’t have any other source of income,” he says. “Stress, when untreated, converts into distress, eventually leading to depression. At an initial stage, depression can be treated with counselling. But one needs medication at later stages, when suicidal thoughts creep in,” he adds.

But in India the lag in crisis-intervention in cases of mental disorders is at 70 to 86 per cent, according to The National Mental Health Survey of 2015-16. Even after the passing of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 , which came into force in May 2018, access to and provision of necessary services to people struggling with a mental disorder remain a challenge.

Seema in her home in Vadgaon in Yavatmal. She has been handling their 15 acres of farmland on her own since 40-year-old her husband, Sudhakar, drank pesticide and ended his life in July 2015

Seema Vani, 42, a farmer in the village of Vadgaon in Yavatmal taluka, is completely unaware of the mental healthcare act, or the services supposedly available under it. She has been handling their 15 acres of farmland on her own since her husband, Sudhakar, drank pesticide and ended his life in July 2015 at the age of 40.

“I have not slept peacefully in a long time,” she says. “I live with tann [stress] . My heartbeats are often racing. Potat gola yeto . I have a knot in my stomach during the farming season.”

Seema had planted cotton when the Kharif season began towards the end of June 2022. She invested Rs. 1 lakh on seeds, pesticides, fertilisers and laboured round the clock to ensure robust returns. She was tantalizingly close to her target, a profit of over a lakh, till two days of massive cloudburst in the first week of September washed away her hard work of the last three months.

“I managed to salvage only Rs. 10,000 worth of harvest,” she says. “Let alone making profits out of farming, I am struggling to break even. You painstakingly cultivate the farmland for months and it all goes bad in just two days. How do I come to terms with it? This is exactly what took my husband’s life.” After Sudhakar’s death, Seema inherited both the farmland and the accompanying stress.

“We had already lost money in the previous season because of the drought,” she says talking about the time before Sudhakar died. “So, In July 2015 when the cotton seeds he had procured turned out to be bogus, it was the last straw. We also had to get our daughter married around the same time. He couldn’t take the stress – it pushed him over the brink.”

Seema had seen her husband become quieter over time. He would keep things to himself, she says, but she didn't expect him to take that extreme step. “Shouldn’t there be some help available to us at the village level?” she asks.

Seema in her home with the cotton salvaged from her harvest

The Mental Healthcare Act 2017 meant that Seema’s family should have had good quality and quantity of counselling and therapy services, half-way homes, sheltered and supported accommodations available to them and within easy reach.

At the community level, the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) introduced in 1996, had mandated every district to have a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, a psychiatric nurse and a psychiatric social worker. In addition, the community health centre at the taluk level should have had a fulltime clinical psychologist or a psychiatric social worker.

But in Yavatmal the MBBS doctors at the Primary Health Centres (PHC) are the ones who identify people with mental health issues. Dr. Vinod Jadhav, DMHP coordinator for Yavatmal, accepts the lack of qualified staff at the PHC. “Only when the case can’t be handled at their [MBBS doctor] level, can there be a referral to the district hospital,” he says.

If Seema were to know and avail of the counselling services at the district headquarters, some 60 kilometres away from her village, she would have to be prepared to take an hour-long bus ride each way, not to mention the expense.

“If the help is an hour-long bus ride, it discourages people from pursuing it because you need recurring visits,” says Kapse. This already adds to the primary challenge of just getting people to admit that they need help.

Jadhav says his team under DMHP conducts an outreach camp annually in each of Yavatmal’s 16 taluks to identify people struggling with mental health issues. It’s better, he says, “to reach out to people where they are, instead of asking them to come to us. We don’t have enough vehicles or funding, but we do as much as we can.”

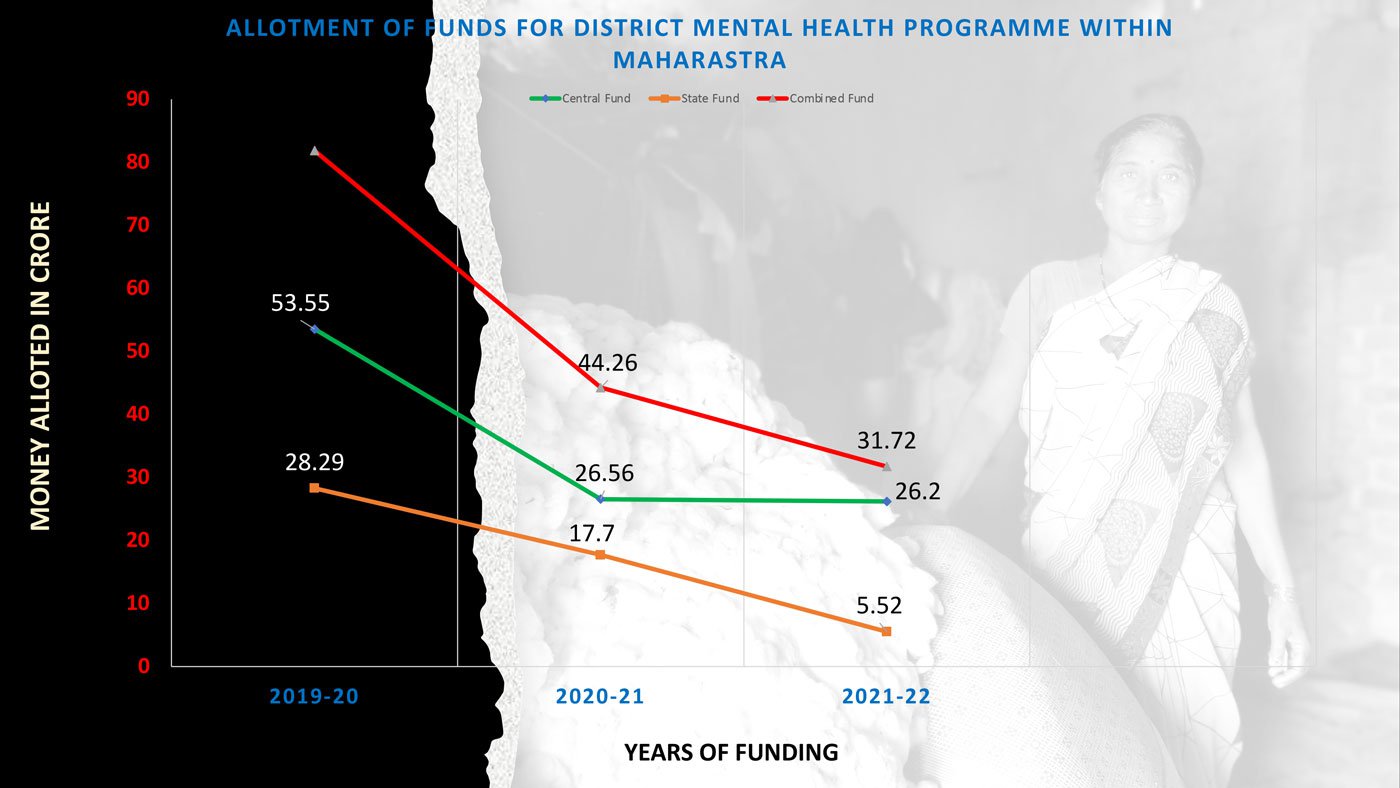

Funds sanctioned by both governments for the state’s DMHP total almost Rs. 158 crore across three years. The Maharashtra government though, spent barely 5.5 per cent of that budget – roughly Rs. 8.5 crore.

The likelihood of the many Vijays and Seemas ever coming across such a camp in unlikely, given the shrinking budget of Maharashtra’s DMHP.

Source: Based on the data collected through the Right to Information Act, 2005, by activist Jeetendra Ghadge

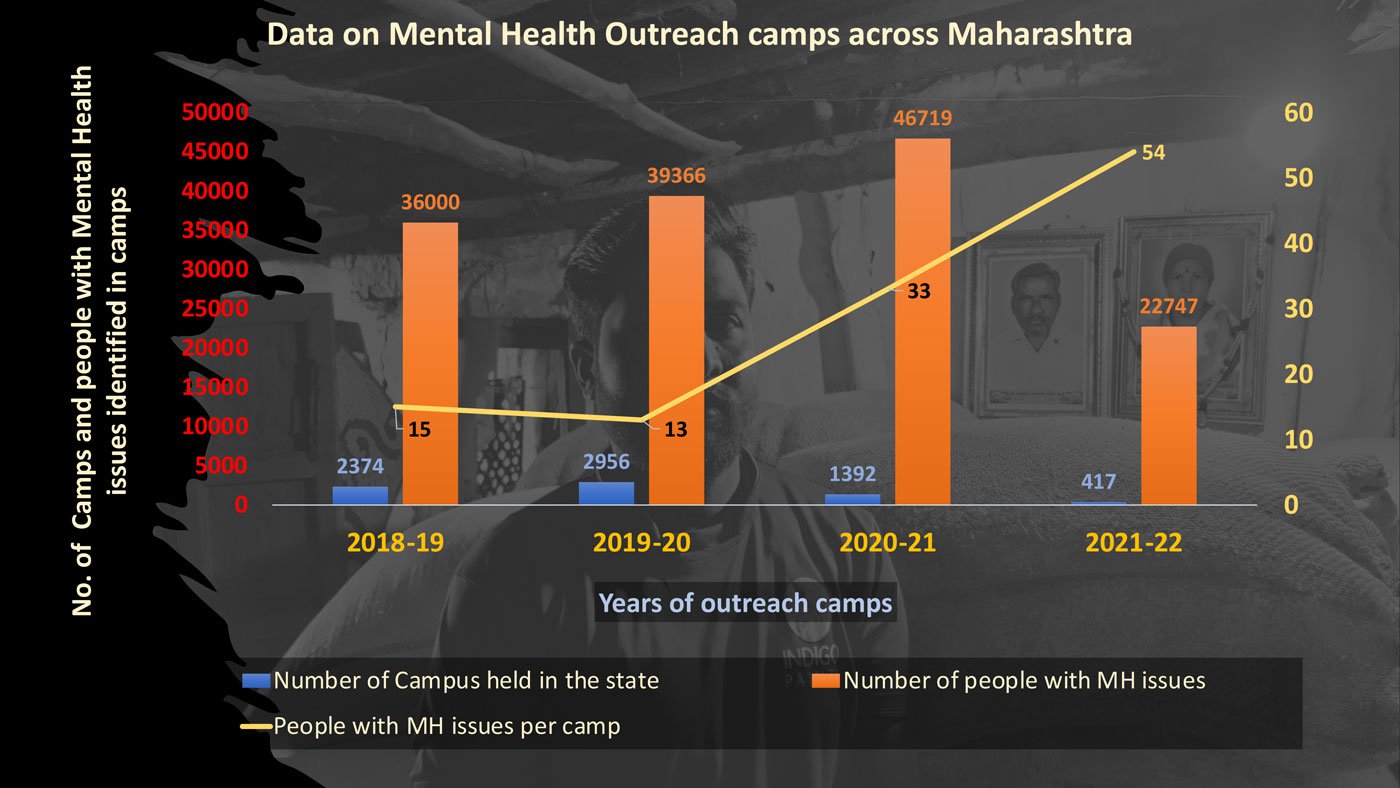

Source: Based on the data collected through the health ministry

The number of camps have decreased over the last few years, in spite of a raging pandemic that exacerbated issues of loneliness, financial strife and mental vulnerability. What has been alarming is the steady upward trend in the numbers of people needing support for mental health.

“Only a fraction benefit from the camps because the patients need recurring visits and camps happen once a year," says Dr. Prashant Chakkarwar, a Yavatmal-based psychiatrist. "Every suicide is a failure of the system. People don’t get there overnight. It is a process made up of several adverse events,” he adds.

And adverse events are increasing in the lives of farmers.

Five months after his father Ghanshyam passed away Vijay Marottar finds himself standing in knee-deep water in his farmland. The excessive rainfall of September 2022 has washed away most of his cotton harvest. It is the first cropping season of his life, where he has no parents to guide or support him. He is on his own.

When he first saw the farmland submerged under water, he didn’t spring into action to salvage it. He simply stood there staring into nothingness. It took him a while to process that his sparkling white cotton had been reduced to rubble.

“I had invested nearly 1.25 lakh [rupees] on the crop,” says Vijay. “I lost most of it. But I have to keep my head. I can’t afford to break down.”

Parth M.N. reports on public health and civil liberties through an independent journalism grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this reportage.

If you are suicidal or know some in distress please call Kiran, the national helpline, on 1800-599-0019 (24/7 toll free), or any of these helplines near you. For information on mental health professionals and services to reach out, please visit SPIF’s mental health directory .