It might be only a matter of time before Padmabai Gajare loses her land. “Had it not been for this land, god knows how we would have survived,” she says.

For eight years after losing her husband Pandharinath, 39, in a motorbike accident, Padmabai has worked tirelessly and stabilised her family, which was reeling from the loss. Pandharinath left behind two sons, two daughters, his mother and 6.5 acres of farmland.

“I was scared and lonely,” she says, sitting in the family’ two-room house in Hadas Pimpalgaon village of Aurangabad’s Vaijapur taluka . “My children were young. I had to take up responsibilities I was not used to. While managing the kitchen, I started operating the farmland as well. Even today, I work as much on the farm.”

Padmabai Gajare (third from left, with her sons and mother-in-law) is worried about the future of her sons if they have no land

But now 40-year-old Gajare might be forced to give up her land. The state government wants it for the Samruddhi Mahamarg (‘prosperity highway’), which will 'connect' 392 villages in 26 talukas , says the Maharashtra Samruddhi Mahamarg website, in 10 districts of Maharashtra. Of these, 63 villages are in the agrarian region of Marathwada, mainly in Aurangabad and Jalna districts.

To build the ‘prosperity’ highway, the state will require 9,900 hectares (around 24,250 acres), says the Mahamarg website. This includes six acres of Padmabai’s farm, where she cultivates cotton, bajra and moong . If forced to give it up, the family will be left with just half an acre. Every time someone mentions the project, Padmabai shudders. “If my land is forcibly taken away from me, I will commit suicide,” she says, “The land is like a child to me.”

In March this year, the Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation Limited (MSRDC) evaluated Padmabai’s land – Rs. 13 lakhs per acre or Rs. 78 lakhs for six acres. That might sound lucrative, but for her it is not about money. “I married off my daughters [now 25 and 22 years old], educated my sons, have looked after my mother-in law, rebuilt this household – all by working on the farm,” she says, furious. “It has held the family together. If the land is gone, what will I have to look forward to? Our land is our identity.”

Padmabai’s younger son is 18, studying science; the older one is 20. Both work on the family farm. “We all know how difficult it is to get a job in today’s world,” she says. “If they don’t get one, they will have to work as daily wage labourers or watchmen in the city. With land of your own, you have something to fall back on.”

The Gajares’ farm in Hadas Pimpalgaon, a village of around 1,250 people, is not far from the existing Mumbai-Nagpur highway. But Devendra Fadnavis, the chief minister of Maharashtra, is promoting the new highway as a project that will change the state’s fortunes. The eight-lane, 120-metre wide, 700-kilometre long expressway will, he claims, boost the economy with swift access for farm produce to ports, airports and agro-processing hubs. The project will reportedly cost Rs. 46,000 crores.

Why are farmers in Marathwada not willing to

sell their land for a seemingly substantial amount when farming has become difficult in most parts of the region?

Of the 9,900 hectares required, 1,000 hectares is already with the state government, including forest department land, the joint managing director of MSRDC, K.V. Kurundkar, told this reporter. The rest has to be acquired. “We have received consent for only 2,700 hectares, and acquired 983 hectares,” Kurundkar says. “We are in the process of acquiring more land. In villages with resistance, we are talking to the farmers and trying to convince them.” The project cannot begin, he says, until the state gets hold of 80 per cent of the land. The plan is to start in January 2018.

Why are farmers in Marathwada not willing to sell their land for a seemingly substantial amount when farming has become increasingly difficult in most parts of the region due to a lack of formal credit systems, erratic weather and low returns on food crops? So much so that it has driven hundreds of farmers to suicide and thousands are in debt.

One reason, as Padmabai points out, is that land has value that cannot be measured in monetary terms. Another major reason is the credibility of the government. Several farmers in debt may well be willing to let their land go, but they don’t trust the state to live up to the promises made ahead of the deal.

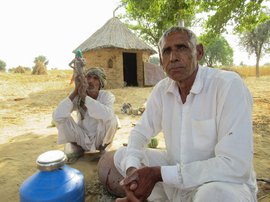

Kakasaheb Nighote, a farmer from Hadas Pimpalgaon, says, 'Look at the track record of any government. They do not care about farmers'

Kakasaheb Nighote, also from Hadas Pimpalgaon, says, “Look at the track record of any government. Does it invoke confidence? They do not care about farmers. There are countless examples across the country where farmers and Adivasis are promised many things before their land is acquired. But in the end it is they who are exploited.”

Forty-year-old Nighote will lose six of his 12 acres to the highway. He shows us the notice served by the MSRDC on March 3 to the village. “The government says we will not do anything without the farmers’ consent,” he says. “But their notice says if you or your representatives are not present on the given day, it will be assumed that you do not require the collective counting of land. We even had to fight for a simple form [at the collectors’ office] that allows us to note our grievances.”Around 35 kilometres from Hadas Pimpalgaon, along the Aurangabad-Nashik highway that runs parallel to the old Mumbai-Nagpur highway, farmers in Maliwada village of Gangapur taluka are in trouble too. A majority of them in this village of around 4,400 people cultivate fruits such as guava, chikoo and figs.

Their farms are located right along the border of Aurangabad and Gangapur. A dusty road, just 10-feet wide, runs through Maliwada separating the two talukas . When the MSRDC evaluated the land in July 2017, land in villages closer to Aurangabad city was deemed more valuable. Maliwada is just 16 kilometres from the city, but because it is not in Aurangabad taluka , the farmers here say they have been offered Rs. 12 lakhs per acre, while farmers with land 10 feet away will get Rs. 56 lakhs per acre.

Balasaheb Hekde, 34, of Maliwada, facing the prospect of losing his 4.5-acre orchard, says, “It [the evaluation] makes no sense. I cultivate saffron, guava and mango. My yearly profits are around what they are offering per acre [Rs. 12 lakhs]. No matter how much money we are offered, how long will that last?”

Balasaheb Hekde, a horticulturalist from Maliwada, says that the farmers of his village resisted when MSRDC officials came to inspect their land

Hekde says though farmers in many parts of Marathwada are struggling, those in villages like Maliwada, with established orchards for horticulture, are financially sound. The Kesapuri dam is close by, the land here is fertile. “Why would anybody sell their land if it is fertile and making money?” he asks. “It requires a lot of investment at first. But if you can sustain that, you are set. My father spent 15 years to set up this orchard. Even if they compensate us with another piece of land, we would have to spend another 15 years to set up an orchard there. And how do we know the new land will be as fertile?

“Farmers do not want to sell their fertile land," reiterates Raju Desle, farm activist with the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and a member of the Samruddhi Mahamarg Shetkari Sangharsh Samiti, which is opposing the project. Besides, the differing deals being offered to farmers are causing a lot of discontent. "At least 10,000 farmers will be displaced [across the state]. The compensation should have been one-project-one-cost,” Desle says. “But some farmers are benefitting a lot, while some are getting a raw deal."

However, MSRDC’s Kurundkar says the land has been evaluated properly and a single rate will be unfair on farmers with land at prime locations. "The disparity is negated when farmers get four times of what their land costs," he says. “Farmers who have sold their land [to us] are content. We gave them four times of the market price and they have even purchased a different plot. Now they have land and also a bank balance.”

Maliwada has since passed a resolution of ‘

gaobandi

’

or a ban on MSRDC officials entering the village. The village, like many others in Marthwada,

observed a ‘Black Diwali’ this year by installing black lanterns in front of

their houses. Desle says 17

gram panchayat

s in Nashik district have passed

a resolution against selling their land.

So instead of this unwanted new highway, Hekde remarks, “The government should fix all the potholes on the old highways.”