Raosaheb Walke was about to leave his farm and head home to Yellori village in Marathwada’s Latur district, when the hailstorm struck on March 15 this year. “It was 19 minutes of mayhem,” he recollects. “The hailstones were huge and struck with force. I survived because I immediately hid under the pile of hay on the farm. There was the sound of birds crying out all around me.”

Nineteen minutes later, when Walke, 70, slid out from under the hay, he could scarcely recognise his farmland. “Dead birds, uprooted trees, destroyed tomatoes and injured animals,” he says. “I could not believe the extent of the devastation. I felt as if I was walking through a morgue of birds; I had to be careful not to step on them.” Nonetheless, Walke says, he was relieved at having avoided a major injury.

His sense of relief did not last long. Walke has land at two different locations, each farm measuring 11 acres. On reaching home, he found that his youngest daughter-in-law, Lalita, 25, had been caught in the storm on the way back from their other farm. “She carried a basket on her head,” says Walke, but there was no place to hide or seek shelter. "The hailstones slammed into her fingers as she held the basket. Three of her fingers came off.”

The Walke family, consisting of 17 people, rushed Lalita to hospital as soon as the storm stopped. “She lost those three fingers of her right hand," says Walke. "She also lost a lot of blood. She is currently at her mother’s place.”

'Dead birds, uprooted trees, destroyed tomatoes and injured animals', Raosaheb Walke of Yellori village says. 'I could not believe the extent of the devastation'

The March 15 hailstorm hit pockets of Latur, Beed and Osmanabad districts in Marathwada. As we drive through Yellori six weeks later, the destruction is still all around us – uprooted trees, broken wires, dented electricity poles and an eerie absence of birds. “Do you see that small group of peacocks?” asks a farmer. “There were over 300 of them before the hailstorm. Now we can barely count 25.”

The devastation completely demoralised farmers ahead of the sowing for the kharif season starting in June. Walke lost 20 tonnes of tomatoes, worth around Rs. 4 lakhs; he was planning to sow wheat, jowar and soyabean for the kharif season.

Gundappa Niture, 60, has still not cleaned up the ruined crop on his 23-acre farm in Yellori. “It is too depressing to walk through my land and relive the experience,” he says, as he leads me into his fields. Wrecked pomegranates rot in the soil, wounded trees all around us, their trunks bearing the marks of the hailstones.

Mid-March, when the storm struck, is when farmers investing in horticulture harvest their produce and get ready for the monsoon sowing season. Horticulture is expensive, but the returns are good. “Pomegranates fetch me 100 rupees a kilo,” says Niture, “and I had 40 tonnes of the fruit. Those 19 minutes cost me 40 lakh rupees.”

Niture's

grapes and tomatoes were ruptured too. Had the hailstorm come just a couple of

days later, he says, he might have saved his crops. “I lost not only my stock, but the 20 lakh rupees I had invested in the crops as well,” he says. “How am I going to revive myself? We had an acute water shortage over the last few years. I bought several tankers of water to keep the plants alive. This year, finally, the crop was promising, but the hailstorm destroyed it all.”

The devastation of the pomegranate crop during the the hailstorm in March cost Niture Rs. 40 lakhs; he lost grapes and tomatoes too, and has a debt of Rs. 17 lakhs

Niture now has a debt of around Rs. 17 lakhs, and a family that includes two sons, a daughter-in-law and a one-year-old grandson. He adds up his loans: “[I took] 8 lakhs from the bank, 5 lakhs in private loan, and I owe various shopkeepers around 4 lakh rupees,” he says. “God bless the shopkeepers. They have not at all pestered me with recovery visits and calls.”

The farmers of Marathwada have experienced hailstorms in the past, but they say the frequency and intensity have been on the rise over the last five years. Even the monsoon patterns have become erratic, Niture points out. “I remember how we used to have a steady drizzle that lasted two or three days,” he says. “It has been years since we experienced that.”

Steady rainfall also helps recharge the groundwater. The pattern these days, however, is of lashing rains for an hour or two and then no rain at all for days. In 2014,

talukas

like Ausa and Parbhani recorded an unprecedented 200 mm rainfall, 123 of that coming down in just 100 minutes.

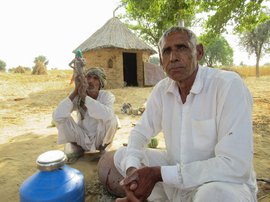

Gundappa Niture at his farm house in Yellori: gearing up for another throw of the dice

Latur-based environmental journalist Atul Deulgaonkar says that even if the total rainfall for the season is adequate, if it is not spaced out, the produce is severely affected. “The erratic weather patterns are a sign of climate change,” he says. “Unseasonal rain through the night and the increased frequency of hailstorms are all indications of it. We need to invest in research to counter climate change.”

In such conditions, farming has become a bit like gambling. Farmers can take crop insurance to cover a disaster, but the method of evaluating crop losses is ludicrous. Just above 1,000 square metres are demarcated to assess a crop in seven villages randomly selected by the district administration from a circle of 40 villages. The crop loss on the demarcated area in those seven villages determines the compensation for the entire circle.

A few farmers in Yellori, who had taken crop insurance last year, opted out of it this year. Shivshankar Onjale says he received only Rs. 14,000 after a hailstorm in 2016. (Crop insurance is a state scheme; farmers pay a premium to insurance companies and the state acts as a bridge). “It added insult to injury,” he says. “I had lost grapes worth 10 lakh rupees. The area of demarcation is quite far from here, and hailstorms are fairly concentrated in the devastation they cause.”

Farmers like Niture and Walke cannot afford to brood over their huge losses; the agricultural cycle must continue and they must try their luck again

To minimise the damage from such hailstorms and other unpredictable weather, in May 2015 Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis had promised to install automated weather stations across the state. These will alert farmers about extreme weather events, so that they can try to take measures to protect their crops. In April this year, Fadnavis inaugurated the first one at Dongargaon near Nagpur.

The government reportedly plans to set up 2065 of these stations to cover 65 lakh farmers across the state’s agrarian regions. Bijay Kumar, Maharashtra's principal agriculture secretary, says 900 have already been installed. "We plan to install all the 2065 stations by August end. The previous system only recorded rainfall, that too was manual. These weather stations help us forecast weather conditions. Every 10 minutes, the weather data is recorded in our systems."

How well these stations function in the remotest villages, and how sustainable they turn out to be, are key to this plan. This year though, the damage has been done, and farmers like Walke and Niture are trying to emerge from the shambles of the storm. They cannot afford to spend time brooding over the damage. “First things first,” says Niture. “I need to clean up the ruined pomegranates. I must gather my wits and look for fertilisers and seeds on credit.”

If the preparations for the kharif season don’t begin on time, Niture risks an unproductive six months. He has no option but to put those 19 minutes behind him. It is time for another throw of the dice.