Inside a tiny hole on the hardened soil lies a dead crab, its legs severed from its body. “They are dying of the heat,” says Devendra Bhongade, pointing at holes all over his five-acre paddy farm.

If it had rained, you’d see crabs swarming in the water on the farm, incubating, he adds, standing amid the drying yellowish-green paddy. “My tillers won’t survive,” is the anxious refrain of this farmer in his early 30s.

In Rawanwadi, his village of 542 people (Census 2011), farmers sow seeds in nurseries – small plots on their land -- in the first half of June, for the arrival of the monsoon. After a few heavy showers, when the furrows bordered by bunds have accumulated muddy water, they transplant the 3 to 4 week-old shoots into their fields.

But even six weeks after the usual start of the monsoon, as late as July 20 this year, it hadn’t rained in Rawanwadi. Twice it drizzled, Bhongade says, but not enough. Farmers who have wells were managing to water the paddy shoots. With work drying up on most of the farms, landless labourers had left the village in search of daily wages.

*****

Around 20 kilometres away, in Garada Jangli village, Laxman Bante too has been witnessing this scarcity for some time. June and July go by without any rain, he says, while the other farmers gathered nod in agreement. And once in 2 to 3 years they almost lose their kharif crop.

Bante, who is around 50, recalls that in his childhood this was not the pattern. The rain was consistent, paddy was steady.

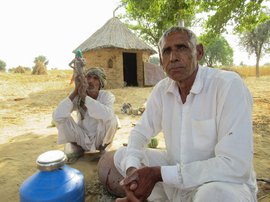

But 2019 has been another year of loss, part of the new pattern. The farmers are anxious. “My land will go fallow in kharif ,” says a fearful Narayan Uikey ( sitting on the floor: see the cover photo ). He is in his 70s and has farmed for over five decades on 1.5 acres, and also worked as a labourer most of his life. “It stayed fallow in 2017, in 2015…” he recalls. “Even last year, my sowing was delayed because of the late rain.” The delay, Uikey says, reduces yields and incomes. Agricultural wage work becomes scarce too when farmers cannot engage labourers for the sowing.

Devendra Bhongade (top left), on his drying farm of

dying paddy tillers in Rawanwadi, pointing to crab-holes (top right). Narayan

Uikey (bottom left) says, ‘If

the rains fail, the farms fail’. Laxman

Bante, farmer and former sarpanch of Garada Jangli, waiting by his village’s

arid farmlands

Garada Jangli is a small village of 496 people in Bhandara taluka and district, around 20 kilometres from Bhandara city. Like in Rawanwadi, most of the farmers here have small plots of land – between one and four acres – and depend on the rains for irrigation. If the rains fail, the farms fail, says Uikey, a Gond Adivasi.

By July 20 this year, the sowing on almost all the farms in his village remained suspended, while the saplings in the nurseries began drying up.

But on Durgabai Dighore’s farm, there was a desperate rush to transplant the half-grown tillers. There is a borewell on her family’s land. Only four or five farmers in Garada have that luxury. After their 80-foot dug-well dried up, the Dighores sank a borewell within the well two years ago, going 150 feet down. When it too became dry in 2018, they got a new one.

Bante says borewells are a new sight here, largely unseen in these parts until some years ago. “In the past, there was no need to bring in a bore [well],” he says. “Now water is difficult to find, the rain is unreliable, so people are getting them [borewells].”

Two small malgujari tanks around the village are also dry since March 2019, adds Bante. Usually, they retain some water even through the drier months. He surmises that the growing number of borewells is drawing away groundwater from the tanks.

These conservation tanks were constructed in the late 17th to mid-18th centuries in the eastern paddy-growing districts of Vidarbha under the supervision of local kings. After the creation of Maharashtra, the state irrigation department took over the maintenance and operation of the big tanks, while the zilla parishads took over the smaller tanks. These water bodies are meant to be managed by the local communities and used for fisheries and irrigation. Bhandara, Chandrapur, Gadchiroli, Gondia and Nagpur districts have around 7,000 such tanks, but a majority have for long been neglected and are in a state of disrepair.

After their dug-well dried up (left), Durgabai Dighore’s

family sank a borewell within the well two years ago. Borewells, people here

say, are a new phenomenon in these parts. Workers on the the Dighores’ farm

(right) could transplant the paddy in July because of the borewell water

Many young men, says Bante, have migrated – to Bhandara city, Nagpur, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, Raipur and other places – to work as cleaners on trucks, itinerant labourers, for farm labour, or to do whatever work they might find.

This growing migration is reflected in population numbers: while Maharashtra’s population grew by 15.99 per cent from Census 2001 to 2011, Bhandara’s grew just 5.66 per cent in that period. The main reason that comes up repeatedly in conversations here is that people are leaving due to the growing unpredictability of agriculture, declining farm work, and an inability to meet increasing household expenses.

*****

Bhandara is a largely paddy-growing district, farmland interwoven with forests. The average annual here ranges from from 1,250 mm to 1,500 mm (notes a report of the Central Ground Water Board). The perennial Wainganga river flows through this district of seven talukas. Bhandara also has seasonal rivers and around 1,500 malgujari water tanks, notes the Vidarbha Irrigation Development Corporation. While it has a long history of seasonal migration, Bhandara has not reported extensive farmers’ suicides – unlike some districts of western Vidarbha.

With only 19.48 per cent urbanisation , it’s an agrarian district of small and marginal farmers, who draw an income from their own land and from farm labour. But without robust irrigation systems, the farming here remains largely rain-fed; tank water is adequate only for some farmlands after October, with the end of the monsoon.

Several reports suggest that central India, where Bhandara is located, is witnessing a weakening of the June to September monsoon and increasing events of heavy to extreme rainfall. A 2009 study by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, speaks of this trend. A 2018 World Bank study finds Bhandara district to be in the top 10 climate hotspots in India, the other nine being contiguous districts in Vidarbha, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, all in central India. A ‘climate hotspot’, the study says, is a location where changes in average weather will have a negative effect on living standards. The study warns of the huge economic shocks that people in these hotspots could face if the present scenario continues.

In 2018, the Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network compiled a fact-sheet on Maharashtra, based on rainfall data of the India Meteorological Department. It explains: One, the frequency and gravity of dry spells increased in almost all the districts of Vidarbha from 2000 to 2017. Two: the rainy days shrank though the long-term annual average rainfall has remained almost constant. This means that the region is getting the same amount of rain in a fewer number of days – and this affects the growth of crops.

Many of Bhandara’s farms, where paddy is usually

transplanted by July, remained barren during that month this year

Another study, done in 2014 by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), notes: “Rainfall data from the period 1901-2003 shows that the share of monsoon rain in July has been decreasing [across the state], while August rainfall has been increasing… Moreover, there has been an increase in the contribution to extreme rainfall events to monsoon rainfall, especially during the first half of the season (June and July).”

For Vidarbha, the study, titled Assessing Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Strategies for Maharashtra: Maharashtra State Adaptation Action Plan on Climate Change, highlights the main vulnerabilities as “long dry spells, recent increase in rainfall variability and decrease in amount [of rainfall].”

Bhandara, it says, is in the group of districts where extreme rainfall could increase by 14 to 18 per cent (relative to baseline), and the dry days during the monsoon are projected to also increase. The study also notes that there will be an average increase (over the annual mean temperature of 27.19 degrees) for Nagpur division (where Bhandara is located) by 1.18 to 1.4 degrees (by 2030), 1.95 to 2.2 degrees (by 2050) and 2.88 to 3.16 degrees (by 2070). This is the highest for any region in the state.

Bhandara agriculture officials too have noticed these incipient changes in their largely rain-dependent district that still gets categorised in government literature and district plans as a ‘better-irrigated’ region due to its traditional tanks, rivers and sufficient rainfall. “We are seeing a steady trend of delayed onset of rains over the district, which hurts sowing and yields,” says the divisional superintending agriculture officer in Bhandara, Milind Lad. “We used to have 60-65 rainy days, but in the last decade or so, this is down to 40-45 in the June-September period.” Some circles – clusters of 20 revenue villages – of Bhandara have got barely 6 or 7 days of rains this year in June and July, he observes.

“You can’t grow fine quality rice if the monsoon is delayed,” adds Lad. “Production drops by 10 kilos per day per hectare if the paddy transplantation is delayed after the 21-day period of the nursery.”

The traditional method of broadcasting seeds – throwing the seeds into the soil rather than planting a nursery first and then transplanting the tillers – is steadily returning to the district. But broadcasting can bring poor yields due to a low rate of germination, unlike the transplantation method. Still, instead of losing the entire crop if the tillers don’t grow in the nursery without the first rains, with broadcasting the farmers could face only a partial loss.

Paddy occupies most of Bhandara’s farms in the

kharif

season

“Paddy needs good rains in June-July for the nursery and transplantation,” says Avil Borkar, chairman of the Gramin Yuva Pragatik Mandal, Bhandara, a voluntary organisation that works with paddy farmers in eastern Vidarbha on the conservation of native seeds. And the monsoon is altering, he notes. Small variations, people can deal with. “But a failure of the monsoon – they can’t.”

*****

By the end of July, the rains have started to pick up in Bhandara. But by thenthe kharif sowing of paddy has been hit – only 12 per cent of sowing was done by the end of July in the district, says Milind Lad, the divisional superintending agriculture officer. Paddy occupies almost all of Bhandara’s 1.25 lakhs hectare cultivable land in kharif, he adds.

Many malgujari tanks that sustain fishing communities are also dry. The only talk among villagers is of water. Farms are the only avenue of employment now. In the first two monsoon months, people here say, Bhandara has not yielded any work for the landless, and even if it rains now, the kharif planting has been irreparably hit.

For acres upon acres, you see empty patches of land – brown, ploughed soil, hardened by heat and a lack of moisture, interspersed with the burning yellow-green beds of the nursery, where the shoots are wilting. Some nurseries that look green are invariably helped by a desperate splash of fertiliser that aids a momentary growth spurt.

Besides Garada and Rawanwadi, some 20 villages in the Dhargaon circle of Bhandara, says Lad, haven’t received good rains this year – and in the past few years too. Rainfall data show that Bhandara faced an overall deficit of 20 per cent from June till August 15, 2019, and a bulk of the 736 mm rain it registered (of the 852 mm long-term average for that period) was after July 25. That is, in the first fortnight of August, the district overcame a big deficit.

Besides, even this rainfall has been uneven, circle-wise data of the India Meteorological Department show. Tumsar, in the north, got good rains; Dhargaon, in the centre, saw a deficit; and Pauni, in the south, received a few good showers.

Maroti and Nirmala Mhaske (left) speak of the changing

monsoon trends in their village, Wakeshwar. Maroti working on the plot where he

has planted a nursery of indigenous rice varieties

However, the meta data don’t reflect the micro-observations of the people on the ground: that the rains come in spurts and in a very short duration, sometime in a few minutes, though the rainfall gets registered for a full day at a rain-gauge station. There are no village-level data on relative temperature, heat or humidity.

On August 14, the district collector, Dr. Naresh Gite, instructed the insurance company to compensate all farmers who had not sown on 75 per cent of their land this year. Initial estimates said such farmers would number 1.67 lakh, with a cumulative unsown area of 75,440 hectares.

By September, Bhandara had recorded 1,237.4 millimetres of rain (starting from June) or 96.7 per cent of its long-term annual average for this period (of 1,280.2 mm). Most of this rain came in August and September, after the June-July rain-dependent kharif sowing was already hit. The rain filled the malgujari tanks in Rawanwadi, Garada Jangli, and Wakeshwar. Many of the farmers attempted a re-sowing in the first week of August, some it it by broadcasting seeds of the early yielding varieties. Yields may be reduced though, and the harvest season may be pushed by a month to late November.

*****

Back in July, Maroti, 66, and Nirmala Mhaske, 62, are troubled. Living with unpredictable rains is difficult, they say. The earlier patterns of prolonged periods of rain – lasting 4 or 5 or even 7 days at a stretch, no longer exist. Now, they say, it rains in spurts – heavy showers for a couple of hours, interspersed with long dry spells and heat.

For around a decade, they haven’t experienced good rains in the Mrig nakshatra , or the period from early June to early July. This was when they would sow their paddy nursery and transplant the 21-day tillers onto the water-drenched plots between bunds. By the end of October, their paddy would be ready to harvest. Now, they wait until November and sometimes even December to harvest the crop. The delayed rains affect per-acre yields and limit their options of cultivating long-duration fine-quality rice varieties.

“By this time [July end],” says Nirmala, when I visited their village, Wakeshwar, “we would be through with our transplantation.” Like numerous other farmers, the Mhaskes are awaiting the showers so that the tillers can be spread out on their farm. For two months, there has practically been no work for the seven labourers who work on their land, they say.

The Mhaskes’ old house looks out to a two-acre farm on which they grow vegetables and local varieties of paddy. The family owns 15 acres. In his village, Maroti Mhaske is known for his meticulous crop planning and high yields. But the changes in rainfall pattern, its growing unpredictability, its uneven spread, has put them in a bind, he says: “How do you plan your crop if you don’t know when and how much it will rain?”

PARI’s nationwide reporting project on climate change is part of a UNDP-supported initiative to capture that phenomenon through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to zahra@ruralindiaonline.org with a cc to namita@ruralindiaonline.org