Sunil Gupta cannot work-from-home. And his ‘office’, the Gateway of India, has been out of bounds for long stretches of lockdown time over the last 15 months.

“This is daftar [office] for us. Where do we go now?” he asks, pointing to the monument complex in south Mumbai.

Until the lockdowns began, Sunil used to wait with his camera from around 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. at this popular tourist spot. As people crossed the checkpoints leading towards the Gateway, he and other eager photographers would greet them with albums of click-and-print instant photos, urging: ' Ek minute mein full family photo' or 'One photo please. Only for 30 rupees'.

After the renewed restrictions in Mumbai from mid-April this year following a surge in Covid-19 cases, they have all again been left with little work. “I walked in here in the morning to ‘No Entry’ stamped on my face,” 39-year-old Sunil had told me in April. “We were already struggling to earn and now we are going into negative [income]. I don’t have the capacity to bear any further losses.”

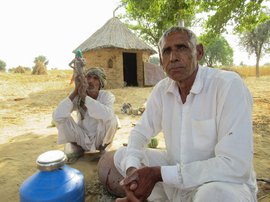

![Sunil Gupta: 'We were already struggling and now we are going into negative [income]. I don’t have the capacity to bear any further losses'](/media/images/02a-IMG_7290-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

![Sunil Gupta: 'We were already struggling and now we are going into negative [income]. I don’t have the capacity to bear any further losses'](/media/images/02b-IMG_7317-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

Sunil Gupta: 'We were already struggling and now we are going into negative [income]. I don’t have the capacity to bear any further losses'

For their ‘office’, when work was available, Sunil and the other Gateway photographers (all men) would usually dress ‘formal’ – neatly ironed white shirts, black pants, black shoes. Each of them had a camera slung around his neck and a bag clinging to their backs. Some would hang a few colourful sunglasses on their shirts to attract tourists who like to get their photos clicked wearing stylish shades. They held in their hands albums full of smiling faces of visitors at the monument.

“Now you will see more of us [photographers] and less of the public,” Sunil says. Before the first lockdown that began in March 2020, he and others here estimate that around 300 photographers worked at the Gateway. Since then, their numbers have fallen to less than 100, with many seeking other work or returning to their hometowns and villages.

Last year, Sunil had re-started work by August. “We kept standing day and night even in the rains, waiting for just one customer. During Diwali [in November] I had no money to even buy a packet of sweets for my kids,” he says. Then he got ‘lucky’, he adds, and managed to earn Rs. 130 that festival day. During that period, occasional financial help had come in from individual donors and organisations who distributed rations to the photographers.

Since he began doing this work in 2008, Sunil’s income had anyway been on a downward sliding scale: from Rs. 400-1,000 a day (or, during major festivals, a high of Rs. 1,500 earned from around 10 photo-seekers) to roughly Rs. 200-600 daily after the proliferation of smartphones with inbuilt cameras.

And after the lockdowns since last year, it’s down to barely Rs. 60-100 a day.

It's become harder and harder to convince potential customers, though some agree to be clicked and want to pose – and the photographer earns Rs. 30 per print

“Going without any boni [first sale and earning of the day] is becoming our daily fate now. Our dhanda had already been on a low for the past few years. But then this [no income days] wasn’t as frequent as it is now,” says Sunil, who lives with his wife Sindhu, a homemaker and occasional tailoring teacher, and their three children in a slum colony in south Mumbai’s Cuffe Parade locality.

Sunil came to this city in 1991 with his mama (uncle) from Farsara Khurd village in Uttar Pradesh. The family belons to the Kandu community (listed as an OBC). His father used to sell haldi , garam masala and other spices in their village in Mau district. “My mama and I set up a thela selling bhel puri at Gateway, or we would sell something or the other – popcorn, ice-cream, nimbu pani . We saw a few photographers working there and I too got interested in this line,” Sunil says.

Over time, he saved, borrowed from friends and family, and in 2008 bought a basic second-hand SLR camera and printer from the nearby Bora Bazar market. (Around the end of 2019, he bought a more expensive Nikon D7200, again after borrowing money; he is still repaying that loan).

When he bought his first camera, Sunil had counted on business booming because photos could instantly be given to customers with portable printers. But then smartphones became easily available – and the demand for his photos dropped steeply. For the past decade, he says, no new entrant has joined the profession. His is the last batch of photographers.

'Now no one looks at us, it’s as if we don’t exist', says Gangaram Choudhary. Left: Sheltering from the harsh sun, along with a fellow photographer, under a monument plaque during a long work day some months ago – while visitors at the Gateway click photos on their smartphones

Now, besides portable printers, to try and match the competition from smartphones, some of the photographers also carry a USB devise so that they can instantly transfer the photos from their camera to the customer’s phone – and charge Rs. 15 for this service. A few customers opt for both – a softcopy as well as an instant hardcopy (for Rs. 30 per print).

Before Sunil began, a generation of photographers at Gateway used Polaroids, but these, they say, were expensive to print and maintain. When they shifted to point-and-shoot cameras, they would send hardcopy photos to the customers by post.

Among the Gateway photographers who briefly used a Polaroid decades ago was Gangaram Choudhary. “There was a time when people would come to us and ask that we take their photo,” he recalls. “Now no one looks at us, it’s as if we don’t exist.”

Gangaram was barely in his teens when he started working at the Gateway, after coming to Mumbai from Dumri village in Bihar’s Madhubani district. He belongs to the Kewat community (listed as an OBC). He had first moved to Kolkata where his father worked as a rickshaw-puller, and found work there as a cook’s assistant for a monthly salary of Rs. 50. Within a year his employer sent him to work at a relative’s place in Mumbai.

Tools of the trade: The photographers lug around 6-7 kilos – camera, printer, albums, packets of paper; some hang colourful sunglasses on their shirts to attract tourists who like to get their photos clicked wearing stylish shades

Sometime later, Gangaram, now in his early 50s, met a distant relative who was a Gateway photographer. “I thought, why not try my hand too at this?” he says. At that time (in the 1980s) he recalls there were only around 10-15 of them at the monument. A few senior photographers would loan their spare Polaroid or point-and-shoot cameras to newcomers for a commission. Gangaram would be asked to hold the photo albums and solicit customers. Gradually, he was given a camera. From the Rs. 20 charged then per photo from customers, he would get to keep Rs. 2 or Rs. 3. He and a few others slept on the Colaba pavements at night and spent their days looking for people to photograph.

“At that age you are just excited to move around to get money in hand,” says Gangaram, smiling. “In the beginning, the photos I took were a bit uneven, but you learn the work as you go along.”

Each reel was valuable – a 36-photo reel used to cost Rs. 35-40. “We couldn’t just keep clicking. Each photo had to be taken with care and thought, unlike today when you can take as many [digital] photos as you want,” Gangaram says. He recalls too that without flashlights in their cameras, they could not work beyond sunset.

It took a day in the 1980s to get photos printed at shops and small photo studios in the nearby Fort area – Rs 15 to develop each reel, Rs. 1.50 to print each 4x5 inch colour photo.

To try and compete with smartphones, some photographers carry a USB devise to transfer the photos from their camera to the customer’s phone

“But now we have to carry all this around to survive,” says Gangaram. The photographers lug around 6-7 kilos – camera, printer, albums, paper (a packet of 50 costs Rs. 110, plus there are cartridge costs). “We stand here all day trying to convince people to agree to a click. My back hurts badly,” adds Gangaram, who now lives in a Nariman Point slum colony with his wife Kusum, a homemaker, and their three children.

In his early years at the Gateway, families would sometimes even take the photographers along to be photographed at other places during their Mumbai darshan tours. The photos were then posted or couriered to the customer. If the images turned out to be blurred, the photographers used to send the cash back in an envelope with an apology note.

“It was all based on trust, and that was a good time. People came from across all states and they valued that photo. For them it was a memory that they wanted to show their families back home. They trusted us and our photography. Our speciality was clicking photos in such a way that in the image it looks like you are touching [the top of] Gateway or the Taj Hotel,” says Gangaram.

But even in their best years of work, there were problems too, he recalls. At times the photographers were summoned to the Colaba police station if a complaint was lodged against them by a peeved customer, or people would return to the Gateway in anger saying they had been cheated and had not received the photos. “Gradually, we started carrying a register with stamps from the nearby post office as proof,” says Gangaram.

And there were times when people didn’t have money for the prints. The photographers then had to take the risk of waiting for the payment by post.

!['Our speciality was clicking photos in such a way that in the image it looks like you are touching [the top of] Gateway or the Taj Hotel'](/media/images/07a-IMG_6170-Crop-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

!['Our speciality was clicking photos in such a way that in the image it looks like you are touching [the top of] Gateway or the Taj Hotel'](/media/images/07b-IMG-20210701-WA0075-Filter-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

'Our speciality was clicking photos in such a way that in the image it looks like you are touching [the top of] Gateway or the Taj Hotel'

Gangaram recalls that after the terrorist attack of November 26, 2008, work stopped for a few days, but slowly demand increased again. “People came to just get clicked alongside the Taj Hotel [opposite the Gateway of India] and Oberoi Hotel [two sites of the attack]. The buildings had a story to tell now,” he says.

Trying for years to frame people into these stories is also Baijnath Choudhary, who works on the pavements outside the Oberoi (Trident) Hotel at Nariman Point, around a kilometre from the Gateway. Now around 57, Baijnath has been a photographer for four decades, though many of his colleagues have sought other livelihoods.

He came to Mumbai at the age of 15 from Dumri village in Bihar’s Madhubani district, accompanying an uncle who sold binoculars on a pavement in Colaba, while his parents, daily wage agricultural labourers, stayed back in the village.

Baijnath, a distant relative of Gangaram’s, also used a Polaroid when he began, then graduated to a point-and-shoot camera. He and the handful of other photographers at that time at Nariman Point left their cameras for safekeeping at night with a shopkeeper near the Taj Hotel while they slept on nearby footpaths.

Baijnath Choudhary, who works at Narmian Point and Marine Drive, says: 'Today I see anyone and everyone doing photography. But I have sharpened my skills over years standing here every single day clicking photos'

Around 6 to 8 customers a day would fetch Baijnath a daily income of Rs. 100-200 in the early years. It increased to Rs. 300-900 over time – but with the arrival of the smartphone fell to Rs. 100-300 a day. And since the lockdowns, he says, it has at times gone down to just Rs. 100 or Rs. 30 a day – or nothing at all.

Until around 2009, he also worked as a photographer in pubs in the Santacruz area in north Mumbai, charging Rs. 50 for each photo “From morning to around 9 or 10 at night I ran around here [Nariman Point]. And after dinner went to the club,” says Baijnath, whose eldest son, 31-year-old Vijay, also works as a photographer at the Gateway of India.

Baijnath and the other photographers say they don’t require permits to operate, but since 2014 have been given identification cards by a group of entities including the Mumbai Tort Trust and the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation. This arrangement also mandates a dress code and a code of conduct that includes being vigilant about unattended bags at the monument, and intervening and reporting instances of harassment of women. (This reporter could not verify these details.)

Before this, at times, they say, the municipal corporation or the cops would charge them fines and stop them from working. To address their concerns collectively, Baijnath and Gangaram recall that the photographers formed a welfare association in the early 1990s. “We wanted some recognition of our work and fought for our rights,” Baijnath says. In 2001, around 60-70 photographers protested at Azad Maidan, he recalls, asking, among other demands, to be allowed to work without undue restrictions and for extended timings. In the year 2000, some of them formed the Gateway of India Photographers Union and, Baijnath says, also met the local MLA with their demands. These attempts brought some respite, and the space to work without intervention from the municipal corporation or local police.

A few photographers have started working again from mid-June – they are still not allowed inside the monument complex, and stand outside soliciting customers

Baijnath misses the early years, when his photography was valued. “Today I see anyone and everyone doing photography,” he says. “But I have sharpened my skills over years standing here every single day clicking photos. We need one click while you youngsters take so many photos to get one correct and then make it more beautiful [by editing],” he says as he gets up from the footpath seeing a group walking by. He tries to persuade them but they are not interested. One of them takes his phone out of his pocket and starts taking selfies.

Back at the Gateway of India, Sunil and a few other photographers have started going to their ‘office’ again from mid-June – they are still not allowed inside the monument complex, so they stand outside, around the Taj Hotel area, soliciting customers. “In the rain you should see us,” says Sunil. “We have to protect our camera, printer, the [paper] sheets. We carry an umbrella on top of all this. We have to balance ourselves holding everything while trying to make the right click.”

But it's the balancing of his earnings that is increasingly even more precarious – when the smartphone-selfie wave and lockdowns have ensured few takers for the photographers’ pleas of ' Ek minute mein full family photo '.

In his backpack, Sunil carries a receipt booklet of the fees paid for his kids (all three study in a private school in Colaba). “I have been asking the school to give me some time [to pay the fees],” he says. Sunil bought himself a small phone last year so that his kids can study online using his smartphone. “Our life is over but at least they shouldn’t burn themselves under the sun like me. They should work in an AC office,” he says. “Every day, I hope to make a memory for someone and in return give my children a better life.”