It was when he saw the blood-soaked stretcher that Srikrishna Bajpayee panicked. “We were warned that the delivery might not be an easy one,” recalls the 70-year-old farmer, warming himself by a fire outside his home on a bitterly cold February afternoon in Uttar Pradesh’s Sitapur district. “The ASHA worker in the village had marked my daughter-in-law’s pregnancy as ‘high-risk’.”

Though it happened in September 2019, Srikrishna remembers it like it was yesterday. “[Flood] waters had just receded, but it had damaged the roads, so the ambulance could not come to our doorstep,” he says. Srikrishna’s hamlet, Tanda Khurd, falls in Laharpur block, which is close to Sharda and Ghaghra rivers. Villages here are vulnerable to recurrent flash floods, making it difficult to arrange transport in emergencies.

The 42-kilometre journey from Tanda Khurd to the District Hospital in Sitapur is long for any pregnant woman in labour – longer if the first five kilometres need to be covered by a two-wheeler on uneven, slippery roads. “We had to do that to get to the ambulance,” says Srikrishna. “But the complications began [to arise] when we reached the district hospital.”

Mamata did not stop bleeding after she gave birth, to a baby girl. Srikrishna says he kept hoping for the best. “It wasn’t unexpected. We knew there might be problems. But we thought the doctors would save her.”

But when she was being moved to a ward on a stretcher, Srikrishna could not see the white sheet on it. “There was so much blood. I felt a knot in my stomach,” he says. “The doctors told us to arrange blood. We managed it quite quickly, but by the time we returned to the hospital from the blood bank, Mamata had died.”

She was 25 years old.

Srikrishna Bajpayee says his daughter-in-law Mamata's pregnancy was marked as 'high-risk', “but we thought the doctors would save her”

Just the day before she died, a medical checkup showed that Mamata weighed 43 kilos. Besides being underweight, she had protein deficiency and her haemoglobin level was at 8 g/dl, bordering on severe anaemia (pregnant women must have a haemoglobin concentration of 11 g/dl or above).

Anaemia is a major public health issue in Uttar Pradesh, especially among women and children, notes the National Family Health Survey 2019-21 ( NFHS-5 ). Over 50 per cent of all women in the age group 15-49 are anaemic in the state.

Nutritional deficiencies are among the most common causes of anaemia. Deficiency of iron is responsible for almost half of all anaemia in the world, but deficits of folate (Vitamin B9) and Vitamin B12 are also important factors besides infectious diseases and genetic conditions.

Only 22.3 per cent of mothers in UP had consumed iron and folic acid supplements for at least 100 days during their pregnancy, NFHS-5 data shows. The national rate is almost double in 2019-21, at 44.1 per cent. But in Sitapur district, only 18 per cent took the supplements.

Anaemia has far-reaching consequences for mothers and babies. It can result in premature delivery and low birth weight, among other effects. Above all, it is directly linked to maternal mortality, and perinatal mortality, that is, stillbirths and early neonatal fatalities.

India’s maternal mortality ratio, or MMR, was 103 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017-19. In the same period, the MMR in UP stood at 167. The state’s infant mortality rate was 41 per 1,000 live births in 2019, 36 per cent more than the national rate of 30.

Srikrishna and his wife, Kanti, keeping warm by the fire. They mostly eat

khichdi

or

dal

rice as they have had to cut down on vegetables

Mamata’s death was not the only tragedy in the Bajpayee family. Her baby girl died too, 25 days later. “We hadn’t recovered from one tragedy when the second one struck,” says Srikrishna. “We were in shock.”

The pandemic was six months away when Mamata and her baby died merely days apart. But when Covid-19 broke out, public health services across the country were impacted, leading to a significant decline in maternal health indicators.

Population Foundation of India analysed data from the Health Management Information System, and noted that between April and June 2020 there was a 27 per cent drop in antenatal care visits received by pregnant women when compared to the same period in 2019. The decline in prenatal care services was 22 per cent. “Disruption in maternal health services, reduction in health seeking behaviour and fear of getting infected from health providers added to pregnancy risks and led to worsened health outcomes for women and infants,” a statement by PFI says.

Pappu and his family experienced the pandemic’s effects firsthand.

His wife, Sarita Devi, was five months pregnant, and anaemic, when the second wave of Covid-19 was at its peak. One evening in June 2021, she felt shortness of breath – an indication of low haemoglobin level – and collapsed at home. “There was nobody at home at the time,” says Pappu, 32. “I had gone out in search of work. My mother was out too.”

Sarita looked completely fine that morning, says Pappu’s 70-year-old mother, Malati. “She even made khichdi for the children in the afternoon.”

Left: Pappu could not get to the hospital in time with

Sarita,

his pregnant wife, because of the lockdown. Right: His mother Malati and daughter Rani

But when Pappu returned home in the evening, Sarita, who was in her 20s, looked pale and weak. “She could not breathe [easily].” So he immediately hired an auto rickshaw to go to Bhadohi – 35 kilometres from Dallipur, their village in Varanasi district’s Baragaon block. “The hospitals here [in Baragaon] were full, and the primary heath centre here has no facilities,” he says. “We thought we should go to a private hospital where we could get proper treatment.”

Inefficient healthcare systems unable to cope with the pandemic have had an adverse effect on maternal health globally. In a meta-analysis of studies from 17 countries published in March 2021, The Lancet reviewed the effects of the pandemic on maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes, and concluded that the pandemic “has led to avoidable deaths of mothers and babies”. Immediate action was required, it said, “to avoid rolling back decades of investment in reducing mother and infant mortality in low-resource settings”.

But the state did not act urgently enough for expectant mothers.

Sarita died in the auto rickshaw even before they could get to the hospital. “We kept getting delayed on the way because of the lockdown,” says Pappu. “There were many checkpoints on the way, which held up the traffic.”

When Pappu realised that Sarita was dead, his fear of the police overpowered the grief of losing his wife. Afraid of what the police would do if they found him travelling with a dead body, he told the auto rickshaw driver to turn around and return to the village. “I made sure that her body was upright when we passed through a checkpoint on the way,” he says. “Luckily, we weren’t stopped and there were no any questions.”

Pappu and Malati took the body to a nearby ghat in Dallipur for the last rites. They had to borrow Rs. 2,000 from relatives for it. “I used to work at a brick kiln but it shut after the lockdown [in March 2020],” says Pappu, who belongs to the Musahar community – one of the most marginalised Scheduled Castes in UP.

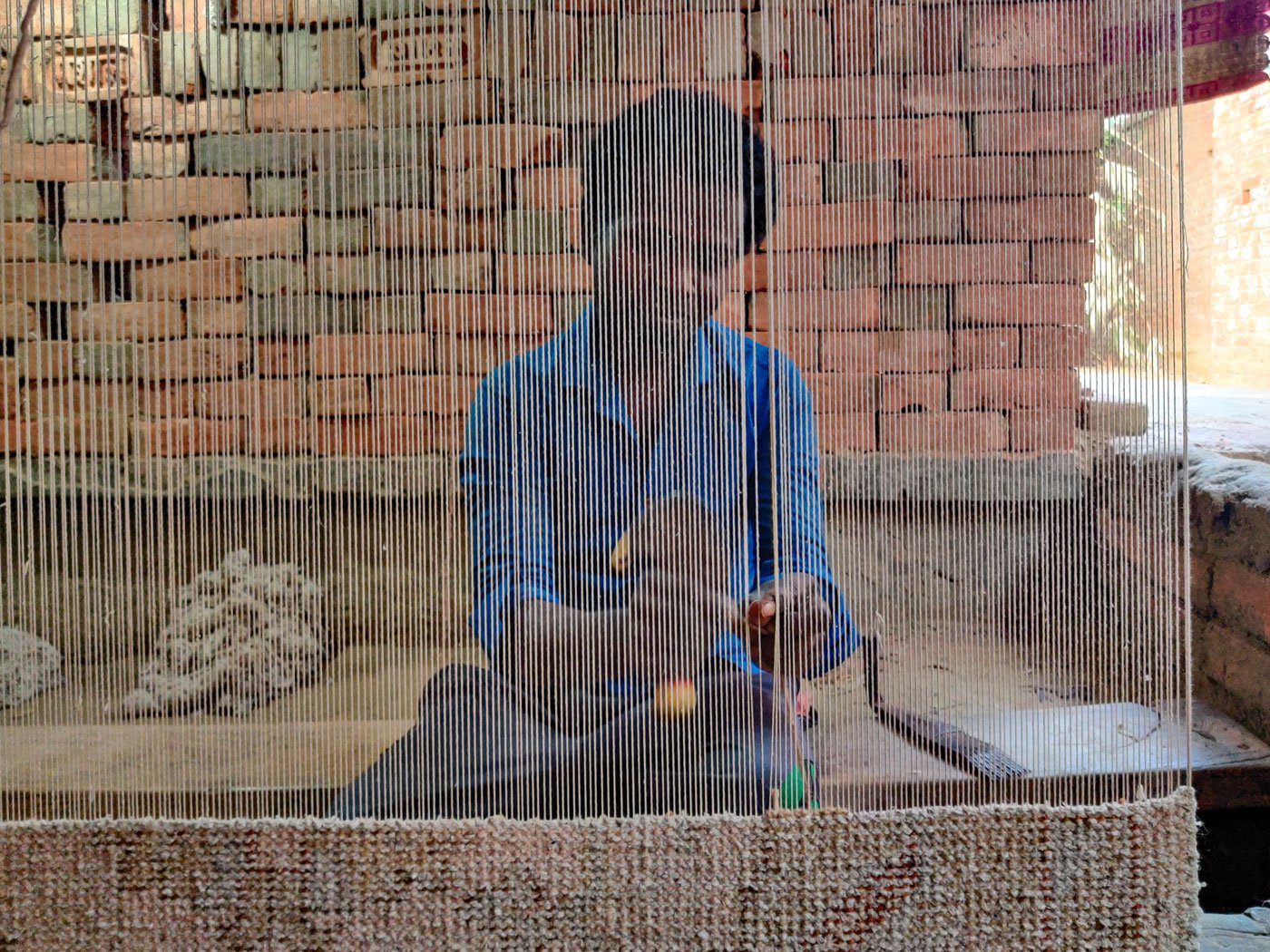

Pappu weaves carpets to earn an income now. He stopped working at brick kilns after Sarita's death to stay home and take care of the children

Before the lockdown, he used to earn Rs. 6,000 a month while working in the kilns. “Brick kilns have reopened, but after my wife’s death I have stopped this kind of work,” he says. “I can’t stay out as much as I used to. I need to be with my children.”

The children, Jyoti and Rani, 3 and 2, watched him fumble while he sat weaving a carpet – his new source of income. “I only started it a few months ago,” he says. “Let’s see how it goes. It allows me to be at home with the children. My mother is too old, she can’t look after them by herself. When Sarita was there, she took care of them along with my mother. I don’t know what we could have done to look after her when she was pregnant. We should not have left her alone.”

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, maternal care in Baragaon block has been neglected even more, says Mangla Rajbhar, an activist associated with the People’s Vigilance Committee on Human Rights based in Varanasi. “Many women in this block are anaemic. They need extra care and rest,” says Rajbhar, who has worked with local communities in Baragaon for over two decades. “But poverty forces the men to leave home and find work [elsewhere]. So women are working at home and in the fields.”

While women need protein, vitamins and iron in their food, they are able to cook just the rations they get through the public distribution systems and can’t afford to buy vegetables, adds Rajbhar. “They don’t have access to advanced healthcare. The odds are stacked against them.”

In Sitapur’s Tanda Khurd, ASHA worker Aarti Devi says several women are anaemic and underweight, creating complications in pregnancy. “People here are only eating dal and rice,” she says. “They are lacking in nutrition. Vegetables are almost missing [from their diet]. Nobody has enough money.”

Income from farming has been in decline, says Srikrishna’s wife, Kanti, 55. “We have only two acres of land, where we cultivate rice and wheat. Our crops are washed away by floods regularly.”

Priya with her infant daughter. Her pregnancy was risky too, but she made it through

Kanti's son Vijay, 33, Mamata’s husband, had taken up the job in Sitapur to escape the family’s dependence on farming for survival, He lost it after the outbreak of Covid-19, but got it back in late 2021. “His salary is Rs. 5,000,” says Kanti. “It sustained us before the lockdown. But we had to cut down on vegetables. It had become difficult to manage [buying] anything other than dal and rice even before the lockdown. Since Covid, we don’t even try.”

The decline in income soon after the outbreak of Covid-19 in 2020 impacted 84 per cent of households across India, a study cites. This, in turn, has affected diet and nutrition.

Rising poverty, inadequate maternal care, and irregular intake of iron and folic acid supplements, will make it tough to reduce high-risk pregnancies, believe Rajbhar and Aarti Devi. Particularly in rural areas, where it is difficult to access public health facilities.

About a year and a half after Mamata’s death, Vijay remarried. His second wife, Priya, was pregnant in early 2021. She was anaemic too, and her pregnancy was also recorded as high-risk. When she was ready to give birth in November 2021, floodwater had just regressed in Tanda Khurd.

The similarity with the day Mamata was taken to hospital was uncanny for Srikrishna. But the flooding was not so bad this time, and the ambulance managed to arrive at their doorstep. The family decided to take Priya to a private hospital 15 kilometres away. She made it through, fortunately, and gave birth to a healthy girl, Swatika. This time around, the odds were in their favour.

Parth M.N. reports on public health and civil liberties through an independent journalism grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this reportage.