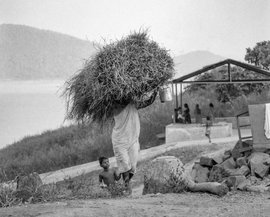

The panel is part of Visible Work, Invisible Women, a photo exhibition depicting the great range of work done by rural women. All the photographs were shot by P. Sainath across 10 Indian states between 1993 and 2002. Here, PARI has creatively digitised the original physical exhibition that toured most of the country for several years.

Bricks, coal and stone

They’re not just barefoot – those are hot bricks on their heads. Those on the ramp are migrants from Odisha working in a brick kiln in Andhra Pradesh. The outside temperature is a scorching 49 degrees Celsius. It’s hotter in the furnace area, where the women mostly work.

A day’s labour fetches each woman Rs. 10-12. Even less than the pathetic Rs. 15-20 the men get. Contractors transport whole families of such migrants here through a system of ‘advances’. These loans tie the migrants to the contractor and they often end up as bonded labourers. Up to 90 per cent of those who come here are landless or marginal farmers.

Despite the open violation of minimum wage acts, none of these labourers can seek redress. The outdated laws covering migrant workers do not protect them. For instance, the laws do not compel the labour department of Andhra Pradesh to help the Odiyas. And the labour authorities of Odisha have no power in Andhra. Bondage also exposes the many women and young girls working in brick kilns to sexual exploitation.

The lone woman making her way through the mud and slush is in the dumps beside the opencast coal mines in Godda, Jharkhand (below right). Like many other women in the area, she scours these dumps for waste coal that can be sold as household fuel to earn a few rupees. If not for people like her, the coal would lie unused there. Her work saves the nation energy, but is criminalised by law.

The maker of tiles lives in Surguja, Chhattisgarh (below right). Her family literally lost its roof after taking a loan they could not repay. The tiles on their roof were the only things they could sell to raise some money and pay off an instalment of the loan. So they did. And now she’s making fresh tiles to replace the old ones.

The stone breaker, from Pudukkottai in Tamil Nadu, is unique (below left). In 1991, some 4,000 very poor women there came to control the quarries where they once worked as bonded labourers. Radical moves by the local administration of the time made that possible. Organised action by the newly literate women made it real. And the lives of the quarry women’s families improved dramatically. Government, too, earned huge revenues from these diligent new ‘owners’. But the process came under savage attack from contractors, who earlier ran illegal quarrying in the region. Great damage has been done. Yet, many of the women have held on to their struggle for a better life.

The women silhouetted against the sunset (below) are leaving the waste dump along the opencast mines in Godda. They have picked up as much waste coal as they could in a day’s work, and are leaving before the monsoon skies open up to trap them in the slush and the slurry. Official counts of the number of women working in mines and quarries are meaningless. That’s because they exclude the many female labourers doing dangerous jobs in illegal mines and their periphery. Like these women striding out of the dumps. They would be lucky to have earned Rs. 10 at the end of the day.

At the same time, they face grave risks from the blasting in the mines, poisonous gases, rock dust and other airborne impurities. Sometimes, 120-tonne dumper trucks come to the edge of the mines and eject ‘overburden’ or topsoil from the dug-up mining area. And some of the poor women racing to grab any waste coal they can from that soil, risk being buried under tonnes of it.