A loud thuk-thuk sound emanates from a corner of a road still quiet at 8 in the morning. Balappa Chandar Dhotre is sitting on the pavement surrounded by big stones, hammering away. The owners of the rickshaws and scooters parked behind his temporary ‘workshop’ will soon be on their way to work. Dhotre too will start moving from here in a few hours – carrying the stone grinders he’s made sitting on that pavement in Kandivali East, a suburb of north Mumbai.

It takes him around an hour to chisel one grinder – or mortar and pestle – used to crush chutneys and masalas. He calls it kallu rubbu , roughly, stone grinder in Kannada, or a khalbatta in Marathi. Once he is done, he puts them in a sturdy rexine bag – usually, 2 to 3 grinders, each weighing between 1 and 4 kilos – and starts walking from his pavement ‘workshop’ to nearby localities. There, at the corners of busy roads, he sets up ‘shop’. He sometimes keeps some kaala patthar (black stone) handy. In case more customers come along asking for grinders, he chisels the patthar on the spot.

“They call me pattharwala only,” says Dhotre.

He sells the smaller stone grinders for Rs. 200 and the bigger ones for Rs. 350-400. “Some weeks I earn up to Rs. 1,000-1,200. Sometimes I don’t earn anything,” he says. The buyers are mainly people who cannot afford an electric grinder, or want to showcase the item in their living rooms, or, like Balappa’s wife Nagubai, prefer using a stone grinder. "I don't like the mixi [electric mixer],” she says, “There is no taste. This [kallu] give food a good taste, it’s fresh."

At the corners of busy suburban roads, Dhotre sets up ‘shop'; his customers are mainly people who cannot afford an electric grinder, or want to showcase the old-style mortar-pestle in their homes, or prefer the taste the stone gives to food

Dhotre no longer remembers his age, but his son Ashok, who is in his mid-30s, says that his father is 66 years old. Although Dhotre retired from the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) as a sweeper in 2011, he prefers to describe himself as a ‘

karigar

’, a craftsman. The stone-work has for long been his family occupation. His father and grandfather all worked with stone in his village, Mannaekhalli, in Homnabad

taluka

of north Karnataka’s Bidar district. The family belongs to the Kallu Vaddar community (listed as an OBC in Karnataka, a subgroup of the Vaddar community of stone workers).

In the 1940s and 1950s, many households used the stone mortar-pestle, and Balappa’s father and grandfather were able to earn a decent income – at that time, he recalls, selling the grinders for 5 to 15 paise a piece. Or they bartered it. “In exchange for this [

kallu

], we would get everything – wheat, jowar, rice, everything.”

When he was around 18, Balappa moved to Mumbai with Nagubai after years of travelling in the villages of Maharashtra to sell the grinders. “I used to travel with my grandfather and father to Beed and Aurangabad districts,” he recalls. “We had a donkey with us. We would place our goods on its back and go from village to village selling the kallu .”

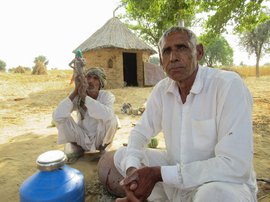

“They call me pattharwala only,” says 66-year-old Dhotre

A drought eventually drove him to Mumbai. “Our village went through a dushkal ,” recalls Balappa, referring to a drought in the early 1970s. The crops wilted and and there was nothing left to eat. “The forests went bare, there was no grass. What would the cattle eat? There was no water, no food, no money [coming in], nothing,” he says. People started moving out. Some sold their lands and migrated to cities. This meant fewer and fewer buyers for the stone grinders. The family, he says, did not own farmland, all he had was the hut where he had spent his childhood. (It is still there, and given on rent to another family.)

Balappa brought along to the big city his father’s and grandfather’s auzaar (implements) – the hammer, chisels, and a spade – to make the grinders

When they first arrived in Mumbai, Balappa and Nagubai stayed near Dadar railway station in a shelter made from sheets. In the following years, they stayed in different parts of Mumbai – Lower Parel, Bandra, Andheri – depending on where his work would take him, setting up a hut wherever they found an empty space.

Nagubai went with him from place to place to sell the mortar-pestles. “My father too used to make

kallu

,” she says. “My mother and I would sell it. After marriage, I used to sell it with him [Balappa]. Now I have back problems and can't do it."

When they first came to Mumbai, Balappa's wife Nagubai (left, with their son Ashok, his wife Kajal, and their kids) went with him to sell the mortar-pestles

But over time, as electric mixer-grinders became more popular, the demand for the stone grinder started falling. Returning to Mannaekhalli – where there was no work for him – was not an option. So Balappa Dhotre stayed on in Mumbai along with Nagubai (over time, they had seven children – three boys and four girls). He started doing odd jobs, sometimes for film shoots in Mumbai. “At that time, they paid 15 rupees a day,” he recalls, to carry the equipment and clean the sets.

One afternoon, when the family was staying near Andheri railway station, the BMC assigned him and other men a cleaning job in Borivali. “They were taken to clean the streets on a temporary basis. Later, the employers thought of making them permanent workers,” says Dhotre’s oldest son Tulsiram, who is in his late-30s.

After getting a BMC employee card, Dhotre was assigned a locality in Kandivali East as his area to clean. He settled with his family in Devipada, at the time a colony of kutcha houses made of bamboo poles and plastic sheets, in nearby Borivali East. As a BMC worker, he initially earned Rs. 500 a month.

Through all this, he continued to make and sell the stone grinders. “He used to leave for [BMC] work at six in the morning,” Tulsiram recalls. “Around 1:30 p.m., mother used to bring his dabba .” The bag with his afternoon meal in the dabba also contained the tools – the hammer and multiple chisels of varying sizes. After his work shift, he would sit down with the stones, and then return home by 5 or 6 p.m.

Balappa brought along to the big city his father’s and grandfather’s auzaar (implements) to make the grinders

The only raw material he needed was the kaala patthar . “You could find it [in the past] by digging into the earth [using a spade and a large hammer],” says Dhotre. Now he procures the stone from the city’s construction sites.

Dhotre retired in 2011 from the BMC after more than three decades of working as a sweeper. His son Ashok says when his father retired his income was around Rs. 18,000-20,000. He now gets a monthly pension of Rs. 8,000.

Ashok inherited his father’s job as a sweeper. Tulsiram does daily wage labour whenever he finds it, as does Dhotre’s third son. His and Nagubai’s four daughters are married and live in various parts of Mumbai. None of the siblings do the family's traditional stone work. “I don't like it, but what to do? They don't want to do it, then they won't do it,” Dhotre says, referring to his sons.

Three years ago, Dhotre and Nagubai had to leave Devipada after a builder promised them a flat in the building once it was ready. Meanwhile, they are staying in a nearby chawl .

Dhotre continues to make stone grinders even though there the number of buyers keeps dwindling. “My father and grandfather used to do it; I too am a karigar , this is who I am,” he says. Adds Nagubai, "He likes to do this, and even I like it that the boodha [old man] is [still] doing some work."