Jasmine is a noisy flower. It arrives early every morning – thump! – at Madurai’s Mattuthavani market in sackfuls of pearly buds. " Vazhi, vazhi [move, move],” men yell as they pour the flowers – swoosh! – on plastic sheets. Sellers gather the delicate flowers, heap it on iron weighing scales – clank! – and tip a kilogram into a buyer's plastic bag. Someone here asks the price, someone there yells the rate; feet scrunch on tarpaulin, squelch on old flowers; agents keep track of the buying and selling, a keen eye, quick scribbles on a notebook, someone shouts "I want five kilos…"

Women shop around for the best flowers. They grab a handful and let it drop through their fingers, checking the quality. The jasmine falls like rain. One flower seller pairs a rose and marigold carefully, parts a hairpin with her teeth. Snap! It’s pinned to her hair. Then she lifts her basket – a colourful medley of jasmine, rose, marigold – on her head, and walks out of the bustling market.

On the roadside, in the small shade of an umbrella, she strings the flowers and sells it by the count –the jasmine buds obediently sitting on either side of the green cotton thread, facing outside, the fragrance gathered inside the petals. And when it blooms – on a plait, inside a car, on an iron nail over a portrait of a God – the scent will announce its name: Madurai malli .

PARI visited Mattuthavani market thrice, over three years. The first visit, four days before Vinayak Chaturthi, Lord Ganesha’s birthday in September 2021, was a crash course in the flower trade. It took place at the back of the Mattuthavani bus-stand, where the market functioned temporarily, due to then prevailing covid restrictions. The idea was to impose social distancing. But it was a bit of a crush anyway.

Before he begins my class, the President of the Madurai Flower Market Association announces his name: “I am Pookadai Ramachandran. And this,” he waves at the flower market, “is my university.”

Farmers empty sacks full of Madurai malli at the flower market. The buds must be sold before they blossom

Retail vendors, mostly women, buying jasmine in small quantities. They will string these flowers together and sell them

Ramachandran, 63, has been in the jasmine trade for over five decades. He began when he was barely a teenager. “Three generations of my family have been in this business,” he says. That is why he calls himself Pookadai , which means flower market in Tamil, Ramachandran, he tells me smiling. “I love and respect my work, I worship it. I’ve earned everything, including the clothes I wear, from this. And I want everybody – the farmers and traders, to thrive.”

It isn’t so simple, though. The jasmine trade is given to price and volume fluctuations, and the volatility can be steep and savage. That’s not all: besides the eternal problems of irrigation, input costs and increasingly unreliable rainfall, farmers also have it rough with labour shortages.

The covid-19 lockdowns proved disastrous. Deemed a non-essential product, the trade in jasmine was hit, affecting farmers and agents very badly. Many cultivators shifted from flowers to vegetables and legumes.

But Ramachandran insists there are workarounds. An efficient multitasker, he keeps an eye on the farmers and their harvests, on the buyers and garland makers, and now and then shouts a “

dei

[hey]” at anybody who is slacking. His solutions to improve the jasmine (

Jasminum sambac

)

production and trade covers both retail and wholesale, and it is highly prescriptive, including a call for a government-run scent factory in Madurai and seamless exports.

“If we do that,” he says, enthusiastically, “

Madurai malli mangadha malliya irukum”

[Madurai’s

malli

will never lose its lustre].” A lustre that is more than just the brightness of the flower and hints at prosperity. Ramachandran repeats this line many times. As if he is manifesting a golden future for his favourite flower.

*****

Left: Pookadai Ramachandran, president of the Madurai Flower Market Association has been in the jasmine trade for over five decades . Right: Jasmine buds are weighed using electronic scales and an iron scale and then packed in covers for retail buyers

In Madurai, jasmine prices vary depending on its variety and grade

By mid-morning, the jasmine trade is brisk. And loud. We shout to be heard above the thrum of voices that rise and engulf us like the scent of the flowers.

Ramachandran buys us tea. And while we drink the hot, sweet liquid, on a hot, sweaty morning, he continues, telling us that some farmers trade in thousands and some go up to 50,000 rupees. "Those are the ones who have planted on many acres. A few days ago, when flowers sold for 1,000 rupees a kilo, one farmer brought 50 kilos." It was like winning a lottery – 50,000 rupees in a day!”

What about the market itself, what is the daily turnover? Ramachandran estimates it to be between 50 lakh and one crore rupees. "This is a private market. There are around 100 shops, and each makes a sale of 50,000 to one lakh rupees per day. You do the math."

Traders earn a 10 per cent commission on sales, explains Ramachandran. “This figure has not changed in decades,” he points out. “And it is a risky business.” When a farmer is unable to pay the money, the trader absorbs the loss. Something that happened often during the covid-19 lockdowns, he says.

The second visit, once again just before Vinayak Chaturthi in August 2022, is to the purpose-built flower market, with its two wide passages, lined on either side by shops. Regular buyers know the drill. Transactions happen quickly. Sackfuls of flowers arrive and leave. The path between the shops is piled high with old blossoms. They squish underfoot, and the sickly smell of old flowers and sharp fragrance of the new fight, for attention. The reason, I later learnt, was because good and bad odours – as we perceive them – depends on the concentration of certain chemical compounds. In this case, it is Indole, which is naturally present in jasmine, as well as faeces, tobacco smoke and coal tar.

At low concentrations Indole has a floral odour, whereas at higher concentrations it smells putrid.

Marigold, roses and other flowers for sale at the market

*****

Ramachandra explains the main drivers of flower prices. For jasmine, flowering begins mid-February. "Until April, the yield is good, but the rate is low. Between 100 and 300 rupees a kilo. From the second half of May, the weather changes and it becomes windy. And there are bigger yields. In August and September, it is the middle season. Production drops by half, and the price doubles. This is when the rate touches 1,000 rupees for a kilo. And in the latter part of the year – November, December – you get just 25 per cent of the average harvest. That's when the prices are astronomical. "Three, four or five thousand rupees for a kilo is not unheard of. Thai maasam [Jan 15 to Feb 15] is also the wedding season, and there is very high demand and very low supply."

Ramachandran estimates the average supply to the primary market in Mattuthavani – where farmers directly bring their produce – to be about 20 tonnes, that is, 20,000 kilos. And 100 tonnes of other flowers. Flowers from here then go to other markets in neighbouring districts of Tamil Nadu – Dindigul, Theni, Virudhunagar, Sivagangai, Pudukkottai.

But the flowering does not follow a bell curve, he points out. "It depends on water, on the rainfall." A farmer with one acre will water a third of that this week, a third the next week and so on, so that he has a [somewhat] steady yield. But when there's rain, everybody's fields are drenched and all the plants flower at once. "That's when rates crash."

Ramachandran has 100 farmers who supply him with jasmine. "I don't plant much jasmine," he says. "It requires a lot of labour." Just the plucking and transport – per kilo – comes to close to 100 rupees. As much as two-thirds of that goes towards labour costs. If the price of the jasmine falls below one hundred rupees a kilo, farmers stand to lose heavily.

The relationship between the farmer and trader is complex. Jasmine farmer P. Ganapathy, 51, of Melauppiligundu hamlet, Thirumangalam

taluka

supplies Ramachandran with flowers. He points out that he takes “

adaikalam,

” or refuge, with the big traders. “During peak flowering, I go to the market so many times – morning, afternoon, evening – with sacks of flowers. I need the traders to help me sell my produce.” Read:

In TN: the struggles behind the scent of jasmine

Left: Jasmine farmer P. Ganapathy walks between the rows of his new jasmine plants. Right: A farmer shows plants where pests have eaten through the leaves

Who sets the price of jasmine? Ramachandran gives me an explanation. “People make the market. People make the money move. And it is very dynamic,” he says. “The rate might start at 500 rupees a kilo. If that lot moves quickly, we immediately jack it up to 600. If we see a demand for that, then we say 800.”

When he was a young lad, "100 flowers went for 2 annas, 4 annas, 8 annas."

Flowers were transported in horse-drawn carts. And in two passenger trains from Dindigul station. “They were sent in bamboo and palm-leaf baskets that keep the flowers ventilated and cushioned. There were far fewer farmers who raised jasmine. And very few were women farmers.”

Ramachandran is nostalgic about the aromatic roses of his childhood, that he calls “

paneer

rose [a very fragrant rose]”. “You can’t find them now! So many honeybees circled each flower, I got stung so often!” But there’s no anger in his voice. Only awe.

With even more veneration, he shows me pictures on his phone of flowers he has donated to various temple festivals: to decorate the chariot, the palanquin, the gods. He swipes through the images, each one grander and more intricate than the other.

But he doesn’t dwell in the past and is clear-eyed about the future. “For innovation and profit, formally educated youth need to come into the business.” Ramachandran might not have fancy college or university degrees, and he is no ‘youth’. But the best ideas for both come from him.

*****

Ramachandran holds up (left) a freshly-made rose petal garland, the making of which is both intricate and expensive as he explains (right)

At first glance, flower strings, garlands and scents do not sound like revolutionary business ideas. But they’re anything but banal. Every garland is at once creative and clever, converting local flowers into aesthetically pleasing strings that can be transported, worn, admired, and composted.

S. Jeyaraj, 38, takes a bus every day from Sivagangai to Madurai, to work. He knows the “A to Z” of garland-making. And has been crafting exquisite ones for about 16 years. He can replicate any design from any photo, he says, with a touch of pride. And that’s besides coming up with original ones himself. For a pair of rose-petal garlands, he earns 1,200 to 1,500 rupees as labour charges. For a simple jasmine garland, it’s between 200 and 250 rupees.

Two days before our visit, there was an acute shortage of garland-makers and flower-stringers, Ramachandran explains. “You need to be properly trained to do it. There’s money to be made,” he insists. “A woman can invest some money, buy two kilos of jasmine and after threading and selling it, she can make a profit of 500 rupees.” This includes her time and labour, which is valued at 150 rupees to string a kilo of Madurai malli , roughly 4,000 - 5,000 buds. Plus, there’s the possibility of a smaller income in retailing the flowers as a ‘kooru’ or heap of 100 flowers.

Stringing flowers calls for speed and skill. Ramachandran gives us a lec-dem. Holding the banana fibre threads in his left hand, he quickly picks jasmine buds with the right, and arranges them next to each other, the buds facing outside, and flips one thread over to hold them in place. He repeats the same for the next line. And the next. And a jasmine garland grows…

Why can't stringing and making garlands be taught at the university, he asks. “It is a vocational and livelihood skill. I can teach too. I can be the correspondent...I have the skills."

The Thovalai flower market in Kanyakumari district functions under a big neem tree

Ramachandran points out that, at Thovalai flower market in Kanyakumari district, stringing buds is a thriving cottage industry. "Strung flowers go from there to other towns and cities, especially to Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam and Cochin in neighbouring areas of Kerala. Why can't this model be replicated elsewhere? If more women are trained, surely that would be a good revenue model. Shouldn't this be there in the home of jasmine?"

In February 2023, PARI travelled to Thovalai market to understand the economics of the town. Not far from Nagercoil, Thovalai town is surrounded by hills and fields and fanned by tall windmills. The market functions under and around a huge neem tree. Strings of jasmine are packed in lotus leaves that are tucked into palm leaf baskets. Jasmine arrives here from the neighbouring Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu and from Kanyakumari itself, the traders – all men – explain. Early February, the rate is 1,000 rupees a kilo. But the big business here is the flowers strung by women. Except there was nobody at the market. Where are they, I ask. “In their houses,” the men tell me, pointing to the street behind.

And that’s where we find R. Meena, all of 80 years old, swiftly picking up jasmine (the variety

pitchi

or

jathi malli

) and threading it together. She’s not wearing glasses. She laughs for many seconds at my surprised question. “I know the flowers, but I can’t see people until they are nearby.” Her fingers work by experience and instinct.

Meena’s expertise though is poorly rewarded. She’s paid 30 rupees to string 200 grams of the

pitchi

variety. That’s approximately 2,000 buds, and she takes an hour to do it. She earns 75 rupees to thread a kilo of Madurai

malli

(roughly 4,000 - 5,000 buds). If she were to work in Madurai, she’d get twice the rate. In Thovalai she makes 100 rupees on a good day, she explains, twisting the jasmine string to make a ball, beautiful and soft and heady.

In contrast, garlands fetch a premium. And it is mostly men who make them.

Seated in her house (left) behind Thovalai market, expert stringer Meena threads (right) jasmine buds of the jathi malli variety. Now 80, she has been doing this job for decades and earns a paltry sum for her skills

In the Madurai region, Ramachandran estimates about 1,000 kilos of jasmine become strings and garlands every single day. But currently, there are plenty of drawbacks. Flowers have to be strung quickly, because in the afternoon heat, " mottu vedichidum ," he says, biting on the words hard to indicate the buds popping. Then they lose value, he points out. "Why can't there be some space allocated for women’s groups in, say, SIPCOT? [The State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu] It can be air-conditioned, so that the flowers remain fresh, and the women can get it done fast, isn't it?" And speed is important, because when it is sent abroad, the flower must reach as a string of buds.

"I have exported jasmine to Canada and Dubai. It takes 36 hours to get to Canada. They must receive it fresh, no?"

Which brings him to transporting flowers. It is not a seamless operation. Flowers are offloaded or have to travel great distances – to Chennai or Kochi, or Thiruvananthapuram – before being airlifted. Madurai has to become an export hub for jasmine, he insists.

His son Prasanna pitches in. “We need an export corridor and guidance. Farmers need marketing help. Plus, there aren't enough packers here for exports. We have to go to Thovalai in Kanyakumari, or Chennai. There are norms and certifications for each country - it will help if guidance on those is given to farmers,” he insists.

Moreover, Madurai malli has a

Geographical Indication

(GI tag) since 2013. But Prasanna does not see it benefitting the primary producers and traders.

Left: The jasmine flowers being packed in palm leaf baskets in Thovalai. Right: Varieties of jasmine are packed in lotus leaves which are abundant in Kanyakumari district. The leaves cushion the flowers and keep them fresh

Ramachandran concludes with the point every farmer – and trader – mentions: Madurai needs its own scent factory. Ramachandran insists that it must be a government-run one. Given the number of times I hear this in my travels in jasmine country, it would appear as if distilling the flowers for its fragrant essence would solve all the problems. Is it the silver bullet that everybody hopes it would be?

In 2022, about a year after we first spoke to him Ramachandran moved to the US where he now lives with his daughter. He has not slackened his grip on matters jasmine a whit. The farmers who supply him and his staff say he is working hard to facilitate exports. Plus, he closely monitors his business and the market from there.

*****

The market as an institution has existed for centuries performing a very important function: that of facilitating commercial exchange, explains Raghunath Nageswaran, a doctoral researcher at Geneva Graduate Institute working on the history of economic policymaking in independent India. “But in the last century or so, it has been projected as a neutral and self-regulating institution. In fact, it has been placed on a pedestal.

“The idea that such a seemingly efficient institution must be left free has been normalised. And any inefficient outcome produced by the market is attributed to unnecessary or misguided state intervention. This stylised representation of the market is historically inaccurate.”

Raghunath explains the “so-called free market,” where “different actors enjoy different degrees of freedom.” If you get to actively participate in market transactions that is, he points out. “There is the so-called invisible hand, yes, but there are also the very visible fists that thump their market power. The traders are central to the functioning of markets, but it is important to recognise the fact that they are powerful actors because they are also storehouses of valuable information.”

One does not need to read academic papers, says Raghunath, “to realise information asymmetry is a great source of power. Such unequal access to information is a function of caste, class and gender factors. We experience it first-hand when we buy physical products from the farm and the factory, or when we download apps on our smartphones, when we access medical services, right?” he asks.

Left: An early morning at the flower market, when it was functioning behind the Mattuthavani bus-stand in September 2021, due to covid restrictions. Right: Heaps of jasmine buds during the brisk morning trade. Rates are higher when the first batch comes in and drops over the course of the day

Left: Jasmine in an iron scale waiting to be sold. Right: A worker measures and cuts banana fibre that is used to make garlands. The thin strips are no longer used to string flowers

“The producers of goods and services also exercise market power because they set the price of their products. That said, there are producers who do not have much control over the price of their output because they are susceptible to monsoon risk and market risk. We are talking about the producers of agricultural goods, the farmers.

“And there are different classes of farmers. Therefore, we need to pay attention to the details,” says Raghunath. “And to the context. Let’s take examples from this jasmine story itself. Should the government directly get involved in perfumery? Or should it intervene by creating marketing facilities and setting-up an export hub for value-added products, facilitating the smaller players in the field?”*****

Jasmine is a costly flower. Historically, fragrant substances – buds and blooms, woods and roots, herbs and oils – have been widely used; in places of worship, to stoke devotion; in the kitchen, to enhance taste; in the bedroom, to sharpen desire. Sandal, camphor, cardamon, saffron, rose and jasmine - they are, among several others, iconic and familiar scents. Because they are commonly used and readily available, they don’t seem exceptional. But the perfume industry would tell you otherwise.

Our education in the workings of the scent industry is just beginning.

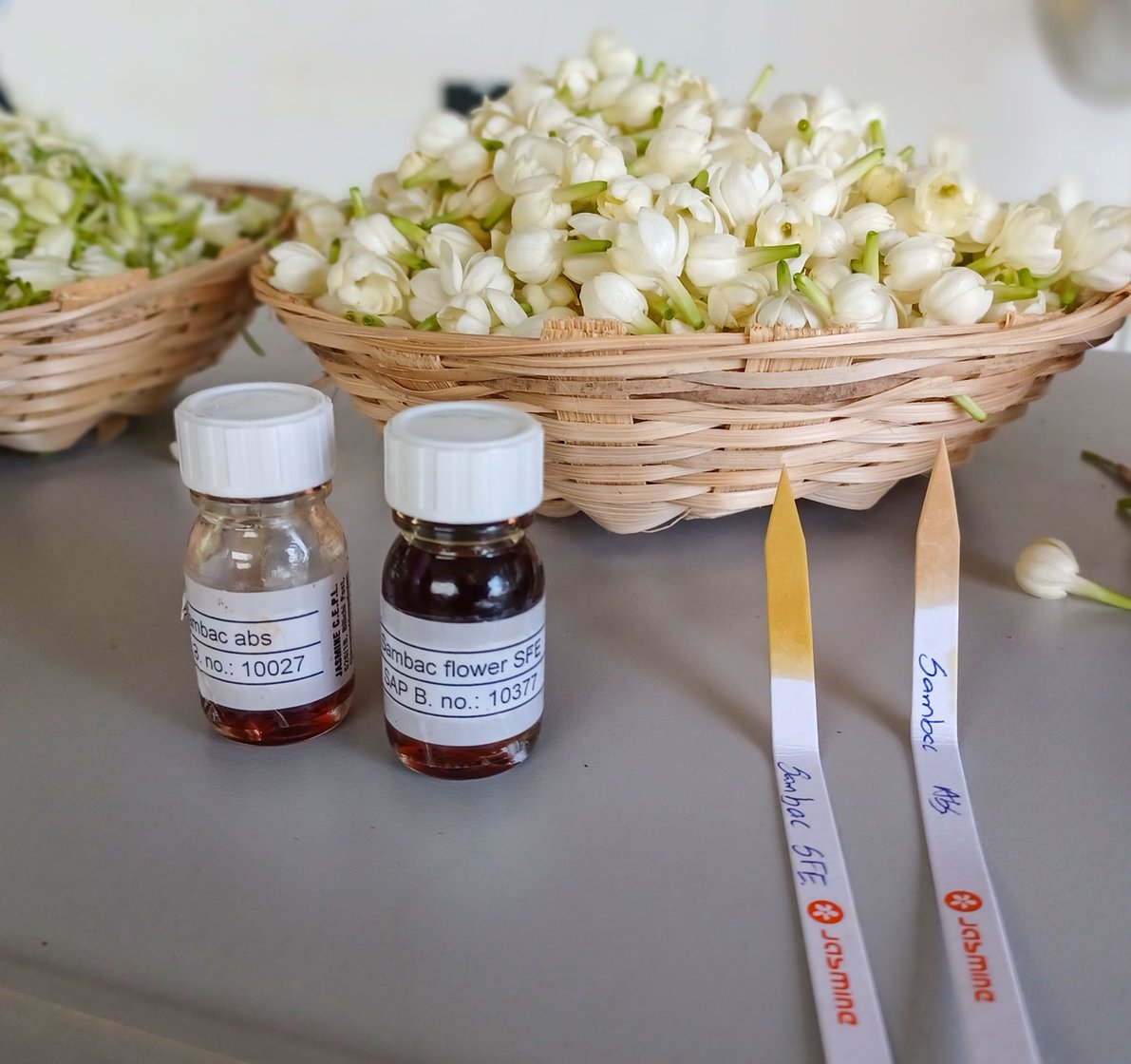

The first and preliminary stage is the ‘concrete’, where the flowers are extracted for their essence using a food grade solvent. The resultant extract is semi-solid and waxy. Once all the wax is removed, it becomes the liquid 'absolute', which is the most user-friendly form of ingredient, as it is soluble in alcohol.

A kilo of jasmine ‘absolute’ is sold for roughly Rs. 3,26,000.

Jathi malli strung together in a bundle

Raja Palaniswamy is Director, Jasmine C.E. Pvt. Ltd (JCEPL). The company is the single largest manufacturer of various floral extracts including the Jasmine sambac concrete and absolute in the world. He explains to us that to get one kilo of jasmine sambac absolute, you need a ton of Gundu malli (or Madurai malli ) flowers. Seated in his Chennai office, he gives me an insight into the global fragrance industry.

Firstly, he points out, “We don’t manufacture perfumes. We produce natural ingredients, which is one of the many components that go into the creation of a fragrance or perfume.”

Among four kinds of jasmine that they process, are two major ones: Jasmine Grandiflorum ( Jathi malli ) and Jasmine Sambac ( Gundu malli ). And the ballpark offer for an ‘absolute’ in the first of these is USD 3,000 a kilogram. For the ‘absolute’ in Gundu malli it’s around USD 4,000 a kilo.

“The prices of the concrete and absolute variants, are solely dependent on the prices of flowers and historically the prices of flowers have only gone up. There could be minor aberrations year on year, but viewed in a long-term trend, the prices have only gone up,” says Raja Palaniswamy. His company, says Raja, processes 1,000 to 1,200 tonnes of Madurai malli (also known as Gundu malli ) annually. That works to around 1 to 1.2 tonnes of jasmine sambac absolute aimed at meeting a global demand of about 3.5 tonnes of jasmine sambac absolute. Altogether, India’s fragrances industry – which includes Raja’s two big factories in Tamil Nadu, plus a few other producers – consume “less than 5 per cent of the total sambac flower production.”

That number was surprising, given that every farmer, every agent, spoke about “scent factories” and how important they were to the business. But Raja only smiles. “We as an industry are a very small consumer of the flowers, but play a key role, to maintain a minimum price for the farmers to ensure they make a profit. Farmers and traders of course would love to always sell at higher prices through the year. It's a flamboyant industry, you know - beauty and fragrance. They think there are big margins, but the fact is, this is a commodity market.”

Pearly white jasmine buds on their way to other states from Thovalai market in Kanyakumari district

It’s a conversation that goes many places. From India to France, and from the jasmine markets in Madurai district, to his clients – including some of the most revered perfume houses in the world: Dior, Guerlain, Lush, Bulgari. I learn a little bit about two worlds that are so removed and yet, somehow, related.

France is the global capital of perfumes. They began sourcing jasmine extracts from India in the last five decades or so. They came looking for Jasminum grandiflorum , or Jathi malli , as it is locally called, explains Raja. “And here, they found a big treasure of many different flowers including many varieties within those.”

The turning point was the launch of J’adore , the iconic French perfume from the house of Dior in 1999. The scent, the perfumer’s note says on their website, “invents a flower that doesn't exist, an ideal.” And this ideal flower includes a dash of Indian Jasmine Sambac , with its “fresh and green notes,” Raja explains, “which became the trend.” And Madurai malli – or as Dior calls it, “Opulent Jasmine Sambac” – found its way to France and beyond, in little glass bottles ringed with gold.

But long before that, the flowers are sourced from the flower markets, in and around Madurai. But not every day. For much of the year, the price of the jasmine sambac is too high to be extracted.

“We need to have a clear understanding of all the factors that influence the demand and supply of flowers into these flower markets,” says Raja. “We have a purchaser / coordinator stationed in the markets and they monitor the prices there very carefully. We have a price that is viable for the trade and wait there after fixing that price at, say, 120 rupees. We have no role to play in the price,” he says adding that the market decides the rate.

“We simply wait and watch the market. And because we have over 15 years of experience in procuring this quantity – the company itself began in 1991 – we can gauge the price for the season. Whenever there is a huge flush, we definitely want the flowers, and we try to maximise our purchase and production.”

Brisk trade at the Mattuthavani flower market in Madurai

It's because of this model that their capacity utilisation is very erratic, Raja points out. “You don't get a standard quantity of flowers every day, it's not like a steel factory where you have iron ore lined up and your machine is running efficiently throughout the year. Here, we just wait for the flowers. So our capacity is built in such a big way to cater to those independent days of flushes.”

In a year, that’s about 20 to 25 big days, Raja says. “Those days we process some 12 to 15 tonnes of flowers, per day. The rest of the time, we get small amounts, ranging from 1 to 3 tonnes, or even nothing at all.”

Raja goes on to answer my question on farmers requesting the government to put up a factory to provide a stable price. “The uncertainty and volatility in the demand might well discourage the government from getting into the ingredients business. While farmers and traders see a potential, there might not be a business case for the government,” Raja argues. “They will be just one more player. Unless they stop everybody else from producing ingredients and establish a monopoly, they will also be procuring from the same pool of farmers and selling the extracts to the same set of buyers.”

To get the best fragrance, jasmine is processed as soon as it blooms, says Raja. “A constant chemical reaction is what helps the flower to smell the way it does when it blooms; the same flower smells bad when it rots.”

To understand the process better, Raja invites me to his perfume factory near Madurai in early February this year.

*****

A relatively quiet day at the Mattuthavani flower market in Madurai

In February 2023 our day there begins in Madurai city with a quick tour of Mattuthavani market. This is my third visit, and it is surprisingly crowd-free and quiet. There is very little jasmine; but there are plenty of colourful flowers: baskets of roses, sacks of tuberose and marigold; heaps of dhavanam (sweet marjoram). Despite the poor supply, jasmine is only trading for about 1,000 rupees. That’s because it isn’t an auspicious day, the traders crib.

We drive out of Madurai city to Nilakottai taluka in neighbouring Dindigul district, to visit farmers who supply Raja’s company with two varieties of jasmine – grandiflorum and sambac . And it is here that I listen to the most astonishing story.

A progressive farmer, with nearly two decades of experience raising malli , Maria Velankanni tells me the secret to a good yield is to get goats to chew up old leaves.

“This only works in Madurai malli ,” he points to his lush green patch of plants growing on one sixth of an acre. “The yield doubles, sometimes triples,” he explains. The process seems unbelievably simple – get a bunch of goats to browse on the jasmine field and eat up all the leaves. Next, leave the field dry for ten days, then fertilise it, and on the fifteenth day, new sprouts appear. By the twenty fifth day, you get a bumper harvest.

With a smile, he assures us it is commonplace in the area. “Goat biting plants to stimulate flowering is traditional wisdom. This novel ‘treatment’ is done thrice a year. Goats in this area eat jasmine leaves during the hot months. Manuring the fields as they browse around, tugging at a leaf here and another there. The goatherds don’t demand a fee – they are just treated to tea and vadai . If they’re penned in the fields in the night, that attracts a charge, something like 500 rupees for a few hundred goats. But the jasmine farmer stands to benefit in any case.”

Left: Maria Velankanni, a progressive farmer who supplies JCEPL. Right: Kathiroli, the R&D head at JCEPL, carefully choosing the ingredients to present during the smelling session

Varieties of jasmine laid out during a smelling session at the jasmine factory. Here 'absolutes' of various flowers were presented by the R&D team

There are more surprises waiting at the factory tour of the Dindigul facility of JCEPL. We are taken around the industrial-scale processing unit, where cranes and pulleys and distillers and coolers make batches of 'concrete' and 'absolute'. There is no jasmine when we visit. In early February, the flowers are too few and terribly expensive; other fragrances are extracted, and the gleaming stainless steel machines hiss, hum and clank, spreading a smell so divine that we all draw in our breaths. Sharply. And smile.

V. Kathiroli, 51, R&D Manager at JCEPL, smiles broadly when he offers us samples of the 'absolutes' to smell. He stands behind a long table, laden with cane baskets of flowers, laminated information sheets about the fragrances, and tiny vials of 'absolutes'. Dipping the tester strips into various tiny bottles, he offers each ingredient eagerly, and notes down every response.

There’s frangipani, sweet and sensual, and tuberose, strong as a punch. Next, he brings out two varieties of rose – one is delicate and fresh, and the other smells comfortingly of straw. Then there is pink and white lotus, both smelling gentle and flowery; and chrysanthemum, which smells exactly as an Indian wedding would, on the tip of a paper.

There are spices and herbs, exotic and familiar, the methi smelling like a warm tadka , the curry leaf like my grandmother’s cooking. The highpoint is jasmine. I struggle to describe the smell. Kathiroli helps me: “floral, sweet, animalic, green, fruity, light-leathery,” he says, without pause. What is your favourite scent, I ask him. I expect a flower.

“Vanilla,” he grins. He and his team have researched and developed the company’s signature vanilla essence. If he were to create a signature perfume, he would use Madurai malli . He wants to be a leader in developing best quality ingredients for perfumery and cosmetics.

Not far from the factory, just outside Madurai city, in the green, green fields, farmers tend to their jasmine plants. The flowers might end up anywhere – inside a frosted glass bottle, a place of worship, a wedding, a wicker basket, on a pavement, in a white coil, smelling divine, as only jasmine can.