Sarika and Dayanand Satpute reluctantly moved house a year ago, in May 2017. “It was a decision based on insecurity and fear,” says 44-year-old Dayanand.

In Mogarga, their village in Maharashtra’s Latur district, the Dalit community had celebrated Ambedkar Jayanti on April 30, 2017. “Every year, we have a programme to mark the occasion some days after Babasaheb’s birth anniversary [on April 14],” says Dayanand

Mogarga village has a population of around 2600 – the majority is Maratha, and around 400 are Dalits, most of them from the Mahar and Matang communities. The Marathas live in the heart of the village, the Dalits on the outskirts. Only a few Dalit families own small plots of land, and most of them work as labourers on the farms of Maratha farmers who mainly cultivate jowar , tur and soyabean here. Or they work as labourers, carpenters and porters in Killari town, 10 kilometres away.

But things got ugly after last year’s function. “A gram sabha [village meeting] was called [by the panchayat ] the day after the function,” says Dayanand. “A few people barged into our homes, threatened us and ordered us to be present. When we [around 15 of us] reached the sabha the next morning, they shouted ‘Jai Bhavani, Jai Shivaji’ slogans to provoke us.” These slogans extol the 17th century Maratha ruler Chhatrapati Shivaji.

An anti-Dalit 'ban' forced the Satputes to move to Indira Nagar in Latur

Dayanand and the others involved in organising the event to celebrate Dr. Ambedkar’s anniversary were asked to explain themselves. “We said it is our right to do so, and something we have always done,” says Dayanand. “A fight broke out and most of our people got badly injured. They already had rods, stones and such things ready…”

“What followed after the gram sabha was absolute injustice,” says Sarika. “Being the dominant community, they barred autorickshaw drivers from giving us a ride, shopkeepers in the village would not sell us anything. We could not buy even basic rations for our kids.” The ‘ban’ impacted all Dalit families in the village.

Police inspector Mohan Bhosale, who handled the Mogarga case – both Dalits and Marathas filed cases against each other at the Killari police station – confirms the incident. But, he says, “Things have been pacified now. We held a joint Diwali celebration in October last year. On Bhaubeej, where a brother gives a gift to his sister, we had Marathas and Dalits exchange token gifts and pledge peace.”

But Dayanand and Sarika are sceptical about this enforced peace. “Another fight broke out [between the two communities] before Diwali after someone said 'Jai Bhim' to another man,” says Dayanand, referring to the Dalit communities’ greeting invoking Bhimrao Ambedkar. “How do you trust the calm when a mere 'Jai Bhim' can flare things up?”

The caste friction in Mogarga speaks of the already deep-rooted caste tensions in Maharashtra that have been aggravated since July 2016 when a minor schoolgirl was raped, mutilated and killed in Ahmednagar district’s Kopardi village. She was from a Maratha community. A special court announced the death sentence for the three accused, all of them Dalits, in November 2017.

The brutal crime triggered several Maratha morchas across the state – and on August 9, 2017, an estimated 3 lakh Marathas marched to Mumbai in protest. They highlighted several demands, but the focus was immediate action against the Kopardi perpetrators.

These protests also voiced and gave heft to the demand to rescind or amend the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act (1989). Upper castes have long claimed that the law is misused by Dalits.

Uday Gaware of the Maratha Kranti Morcha, a Latur-based lawyer who takes up “fake’ atrocity cases for free, condemns the assault on Dalits at the Mogarga gram sabha , but says the ‘ban’ in the village was a reaction to the misuse of the Atrocities Act. “Cases of atrocity were lodged against even those who wanted to solve the dispute,” he says. “We want the strictest of action against Marathas when the cases are genuine. But if the case is false, the accused should be compensated.”

Agrarian distress combined with discrimination has driven many families like Kavita Kamble's from their villages to Buddha Nagar in Latur town

The tensions between the two communities reached a stage in Mogarga where a fearful Sarika would not let her daughters, aged 12 and 11, leave the house. “We had to walk out of the village to buy the smallest thing,” she says. “When my father-in-law needed medicines for his high blood pressure, the chemist did not sell it to him. He walked five kilometres to purchase them [from a store outside the village]. Nobody hired us for work. Survival became difficult.”

The entire community faced this for more than a month, Sarika says. By the end of May 2017, she and Dayanand packed their bags and moved with their daughters to the India Nagar colony in Latur town. They enrolled the girls in a school in Latur. “We do not have land of our own,” says Dayanand. “We worked as labourers there, we work as labourers here. But it is a more difficult life here because the expenses are more.”

Every morning since then, both husband and wife leave home to search for work in town. “It is tougher than in the village,” says Dayanand. “I get work thrice a week on around 300 rupees a day [as a labourer or porter]. We have to pay a rent of 1,500 rupees. But at least I am not insecure about my family.”

The Satpute family’s move speaks of a larger migration of Dalits to towns and cities. While agrarian distress is driving large numbers from all communities out of their villages, there is a difference, says Pune-based law professor Nitish Navsagare of the Dalit Adivasi Adhikar Manch. “The difference between the migration of Dalits and others is that others [usually] own land, so they take longer to leave the village. Dalits are the first to migrate. They have little to go back to. Most of the time, only their elders stay back."

Data of the

2011 Agriculture Census

clearly shows how little land Dalits in India own. Of the 138,348,461 operational land holdings

in the country, Scheduled Castes held only 17,099,190 or 12.36 per cent. Of the total 159,591,854 hectares of land holding, Dalits owned only 13,721,034 hectares – or 8.6 per cent.

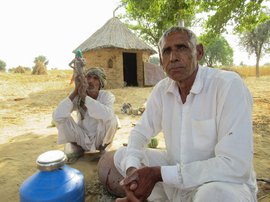

In Buddha Nagar, Keshav Kamble (left) says the Dalit population is growing; Lata Satpute (right) speaks of the daily atrocities against her community

The migrations of Dalit communities, says Manish Jha, dean, School of Social Work at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, are driven by growing agrarian distress as well s discrimination. “Their exploitation or discrimination in the villages creates a sense of humiliation or exclusion,” he says. “On top of that, the Dalits do not own land. And their ability to work as wage labourers decreases because there is no work during drought or agrarian distress in general.”

In Buddha Nagar in Latur, where only Dalits reside, Keshav Kamble, 57, says the population is growing with each passing year. “Currently, over 20 thousand people live here,” he estimates. “Some have come [from their villages] decades ago, some have come days ago.” Almost all the families in the colony are daily wage labourers, like Kavita and Balaji Kamble, who came here five years ago from Kharola village, 20 kilometres from Latur. “We work as coolies, construction labourers – whatever is available,” says Kavita. “In the village those who owned the land would decide whether we get work or not. Why be at the mercy of others?”

Back in Mogarga, a year later, the caste tensions persist, says Yogita, Dayanand’s brother Bhagwant’s wife, who continues to live in the village with her husband and his parents. “They are old," she says. "They did not want to leave the village because they have spent their entire life here. My husband works as a labourer mostly outside the village. We do get work in the village but not as much as we used to. We are still treated coldly. So we also mind our own business."

The Mogarga incident is one of around 90 caste crimes in Latur since April 2016, according to the district social welfare department, though not all of them registered under the Atrocities Act. These do not include what Lata Satpute, 35, goes through every day. Satpute, an occasional farm worker, whose husband is a daily wage labourer in Latur town, six kilometres from their village Warwanti, has to walk an extra three kilometres for water [to a well outside the village] even though a common well is right outside her home. “We are not allowed to wash our clothes or fill water here,” she says, asking her daughter to keep an eye on whether neighbours have noticed she is speaking to a journalist. “Let alone entering the temple, we are not even allowed to walk in front of it.”