The panel is part of Visible Work, Invisible Women, a photo exhibition depicting the great range of work done by rural women. All the photographs were shot by P. Sainath across 10 Indian states between 1993 and 2002. Here, PARI has creatively digitised the original physical exhibition that toured most of the country for several years.

Mud, mothers, 'man hours'

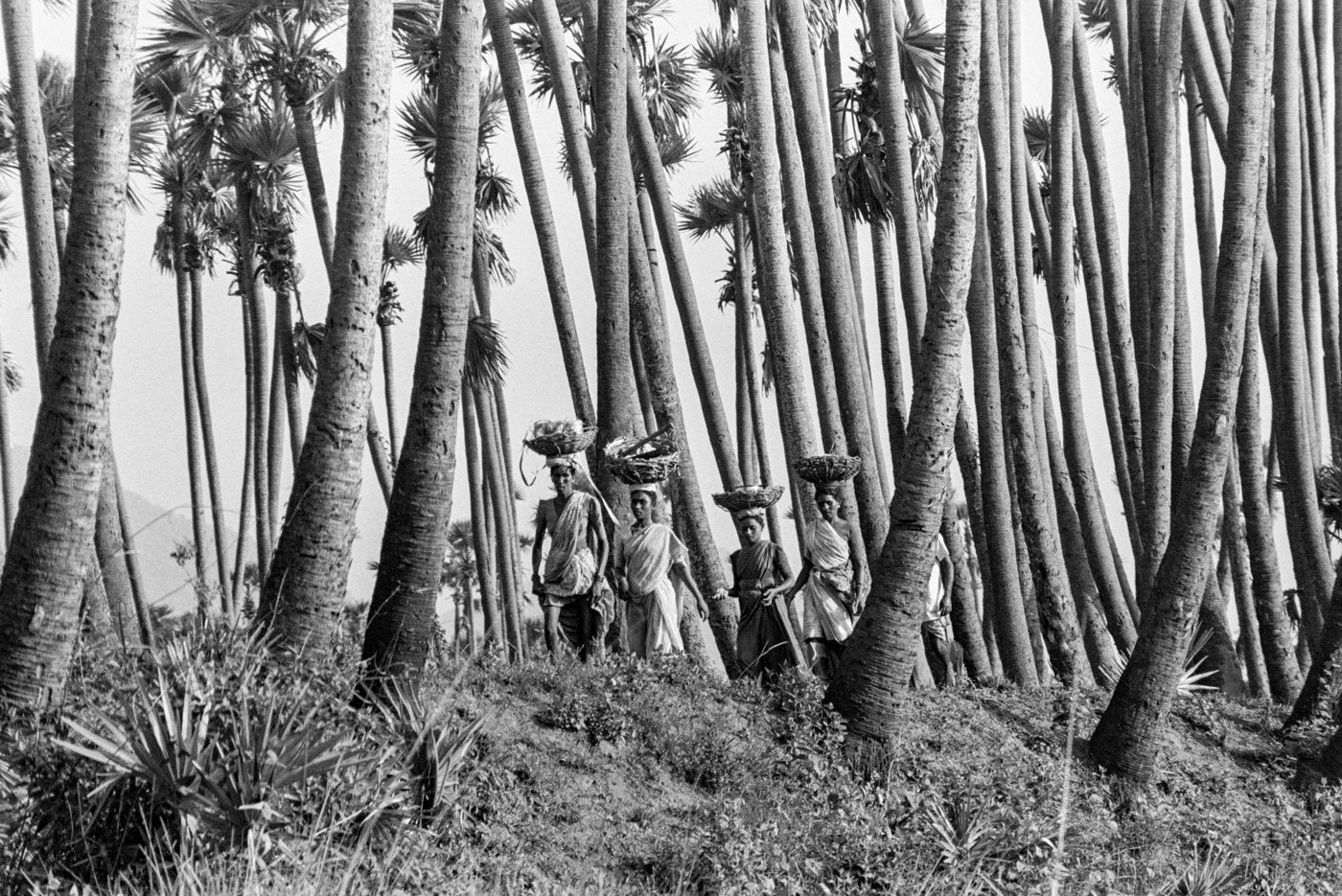

The meeting with landless labourers in Vizianagaram in Andhra Pradesh had been fixed for just before 7 a.m. The idea was to track their work through the day. We were late, though. By that time, the women had put in about three hours. Like those coming to the fields through the palm trees. Or their friends already at the site, removing the mud from a silted tank.

Most had finished cooking, washing utensils and clothes, and some other chores. They had also got the children ready for school. All members of the family had been fed. Of course, with the women eating last. At the government’s employment assurance site, it’s clear the women are paid less than men.

It is also clear that the Minimum Wages Act here is being violated for both men and women. Like it is across most of the country, barring states like Kerala and West Bengal. Yet, women workers get half or two-thirds the wages men do, everywhere.

With the number of women agricultural labourers rising, keeping their wages low benefits landowners. It keeps their wage bills down. Contractors and landowners argue that women perform easier tasks and are therefore paid less. Yet, transplantation is hazardous and complex. So is harvesting. Both expose women to multiple ailments.

Transplantation is in fact a skilled job. Seedlings not planted deep enough or placed at the wrong distance could fail. If the ground is not smoothened properly, the plant cannot grow. Transplantation also requires bending over most of the time in shin-deep to knee-deep water. Yet, it is seen as an unskilled job and paid lower wages. Simply because it’s women who do it.

Another argument for giving women lower wages is that they can’t do as much as men can. But there’s no proof to show that the amount of paddy harvested by a woman is less than that harvested by a man. Even where they perform the same tasks as men, women are paid less.

Would landlords hire so many women if they were less efficient?

In 1996, the Andhra Pradesh government set out minimum wages for

malis,

tobacco pluckers and cotton pickers. These were much higher than those that workers in transplantation and harvesting activities were getting. So discrimination is often pretty overt and ‘official'.

Wage rates, then, may have little to do with productivity. They are often based on long-standing prejudices. On age-old patterns of discrimination. And their acceptance as normal.

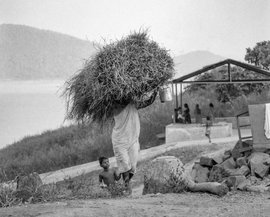

The backbreaking work women do in the fields and other work sites is visible. All this does not exempt them from being chiefly responsible for their children. The Adivasi woman has brought two of hers to a primary health centre in Malkangiri, Odisha (below right). Trudging several kilometres across rough terrain to do so. And carrying her son most of the way. That, after putting in hours of work on a tough, hilly slope.