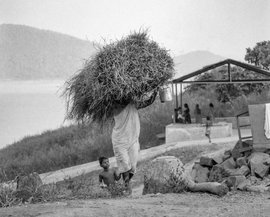

The panel is part of Visible Work, Invisible Women, a photo exhibition depicting the great range of work done by rural women. All the photographs were shot by P. Sainath across 10 Indian states between 1993 and 2002. Here, PARI has creatively digitised the original physical exhibition that toured most of the country for several years.

Cleaning up!

The elderly woman in Vizianagaram in Andhra Pradesh keeps her house and its surroundings spotlessly clean. That’s house work – and 'women’s work.' But whether at home, or in public spaces, the bulk of the dirty work of ‘cleaning up’ is done by women. And they earn more wrath than revenue from it. Those like the one from Rajasthan have it especially bad. She’s a Dalit. A ‘manual’ scavenger who cleans dry latrines in private households. She performs this task for about 25 households in Sikar in Rajasthan every day.

This fetches her a payment of one roti a day from each household. Once a month, if they feel generous, they might even give her a few rupees. Maybe Rs. 10 a house. Officialdom calls her a ‘Bhangi,’ but she terms herself a ‘Mehter'. Increasingly, several among such groups call themselves ‘Balmikis'.

That’s human excreta she’s carrying in the container on her head. Polite society calls it ‘night soil'. She’s among India’s most defenceless and exploited citizens. And there are hundreds like her in Sikar, Rajasthan, alone.

How many manual scavengers does India have? We don’t really know. Right up to the 1971 Census, theirs was not even listed as a separate occupation. Some state governments simply deny the existence of 'night soil' workers. Yet, even the flawed data that exists suggests that close to a million Dalits work as manual scavengers. The real figure could be higher. Those dealing with ‘night soil’ are mostly women.

Their work draws the worst penalties of ritual “pollution” in the caste system. Untouchability on a large and systemic scale haunts every space of their existence. Their colonies are more sharply segregated. Many are somewhere between rural town and city. In villages that have become ‘towns’ without planning. But there are some in the metros as well.

In 1993, the central government passed the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act. This banned manual scavenging. Many states responded by simply denying the existence of the practice in their territories, or with silence. Funds for their rehabilitation exist and are accessible to state governments. But how can you fight something you claim does not exist? In some states there was actually resistance at the Cabinet level to the adoption of the Act.

Women ‘ safai karamcharis’ (sanitation workers) in many municipalities are so poorly paid that they do ‘night soil’ work on the side to make ends meet. Often, municipalities do not pay their salaries for months. In 1996, the safai karamcharis of Haryana launched a huge protest against such treatment. In response, the state government locked up nearly 700 women for close to 70 days after invoking the Essential Services Maintenance Act. The only demand of the strikers was: pay us our salaries on time.

There is a good deal of social sanction for this work. And social reform is necessary to end it. Kerala in the 1950s and ‘60s got rid of ‘night soil’ work without legislation. Public action was, and remains, the key.